John Tolley, July 2, 2019

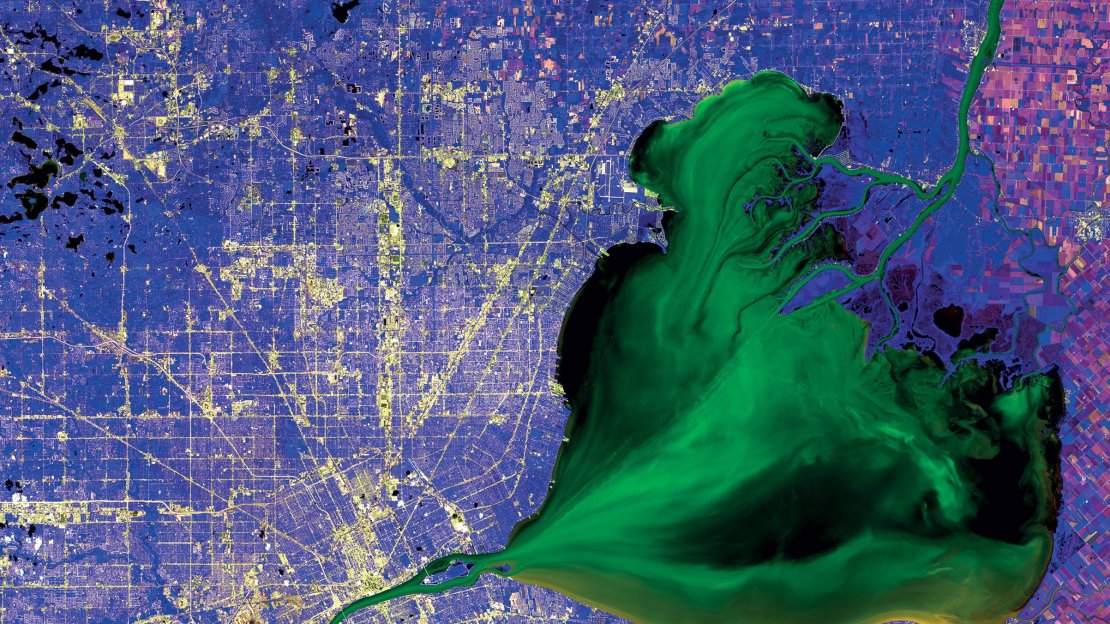

Of all of the narrow passages that connect the Great Lakes, perhaps none is more important, more storied, more trafficked and more imperiled than that which connects Lakes Huron and Erie, separates two nations and gives its name to the most populous city to sit on its shore.

From Port Huron in the north to Pointe Mouillee at the entrance to Lake Erie, the combined waterways of the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River have long been a superhighway of commerce and an economic engine for Southeast Michigan. But the toll of progress along this busy 70-plus stretch of water has been great, indeed.

In his new book The Heart of the Lakes: Freshwater in the Past, Present and Future of Southeast Michigan (Michigan State University Press, 2019), author Dave Dempsey outlines the rich and turbulent history of the are that early French coureurs des bois called De Troit, ?The Straits.? From those heady early days when the dense forests of Southeast Michigan were plundered for lumber and boats built in Marine City sailed out for points west, this vital waterway has come to define the region, for good and ill.

In his new book The Heart of the Lakes: Freshwater in the Past, Present and Future of Southeast Michigan (Michigan State University Press, 2019), author Dave Dempsey outlines the rich and turbulent history of the are that early French coureurs des bois called De Troit, ?The Straits.? From those heady early days when the dense forests of Southeast Michigan were plundered for lumber and boats built in Marine City sailed out for points west, this vital waterway has come to define the region, for good and ill.

Dempsey offers readers a trip through the twin rivers and lake, but also through time itself. We see the area?s lush and ample resources marshalled by the manifest destiny of European settlers. Eventually the churning engines of change brought mass industrialization on a scale never before seen to the shores. By the early 20th century, the waterway was effectively poisoned by unchecked factory runoff and the raw sewage of swelling cities. When frozen over, enterprising rum runners would cart illicit Canadian spirits to thirsty Detroiters during prohibition.

But industry has waned and public knowledge of the environmental abuse of the area has waxed leading to one of the largest remediation programs in US history. Decades of infrastructure updates, tighter pollution controls and wholesale removal of tainted river muck have given rise to vast improvements. Wildlife has returned to a degree; children can once again swim in the water. But there is still much left to be done.

With massive freighters still plying the waters and town and cities pumping out the water and ejecting back in sewage, albeit treated now, Dempsey acknowledges that the waterway will forever hold industrial and civic utility. But his argument for responsible stewardship is simple: as goes the environmental health of the rivers and lake, so goes the economic health of the entire region.