John Tolley, January 15, 2019

On the outskirts of our solar system, a tiny, ancient, bi-lobed body known as Ultima Thule creeps around our sun. It inhabits a cosmic backwater known as the Kuiper belt, where misshapen globs of rock and ice and dwarf planets rule the roost.

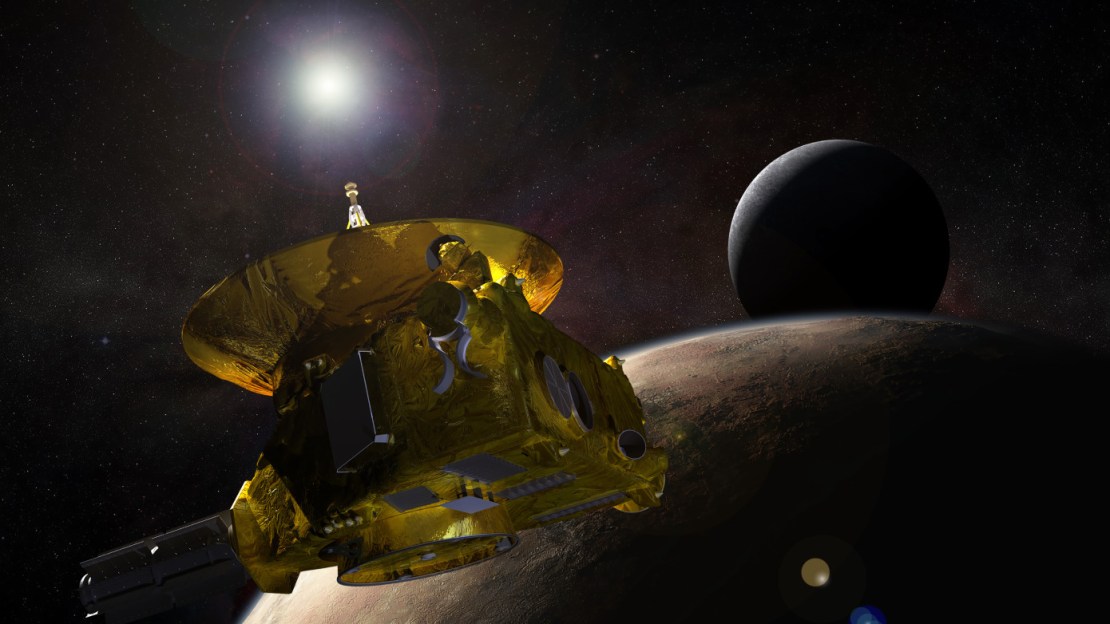

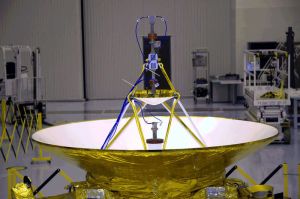

Ultima Thule - formally known as (486958) 2014 MU69 - holds a significant distinction, though, as it recently became the most distant object in our solar system visited by spacecraft. On New Year?s Day, images of the contact binary body beamed from the New Horizons probe were received by NASA, no small feat considering it?s a journey that takes light 4.5 hours to make. And, the high gain antenna that made that incredible journey possible was partially designed and tested at The Ohio State University.

Work on the antenna dates back to 2002, when Ohio State electrical engineering alumni Ron Schulze and Willie Theunissen, who are now with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, conceived the highly focused radio wave transmitter. The pair were able to fine-tune and calibrate the antenna at Ohio State?s ElectroScience Laboratory Anechoic Chamber.

Though New Horizon?s mission peaked three years ago when the probe sent back stunning images of the surface of dwarf planet Pluto, the flyby of Ultima Thule is even more demanding of the spacecraft?s equipment. More than a billion miles further out into space, communication requires the antenna to be pointed within .001 degrees of Earth and takes 6 hours to reach Earth. Still, the device accurately transfers data at a rate of 1,000 bits per second.

For now, New Horizon?s mission will be to continue to transmit data from the Ultima Thule flyby back to Earth, a process that will take 20 months in total. But scientists at NASA are hopeful that the probe will be assigned a new mission that will take it even further into the Kuiper Belt and the space beyond. If so, a piece of Ohio State technology will be there to tell us all about it.