Betsy Piland, July 14, 2018

In a sophisticated, urban health care setting, it?s not uncommon for the maintenance of everyday medical equipment to be costly. Now, move those same challenges to a rural East African hospital and the problem just became cost prohibitive.

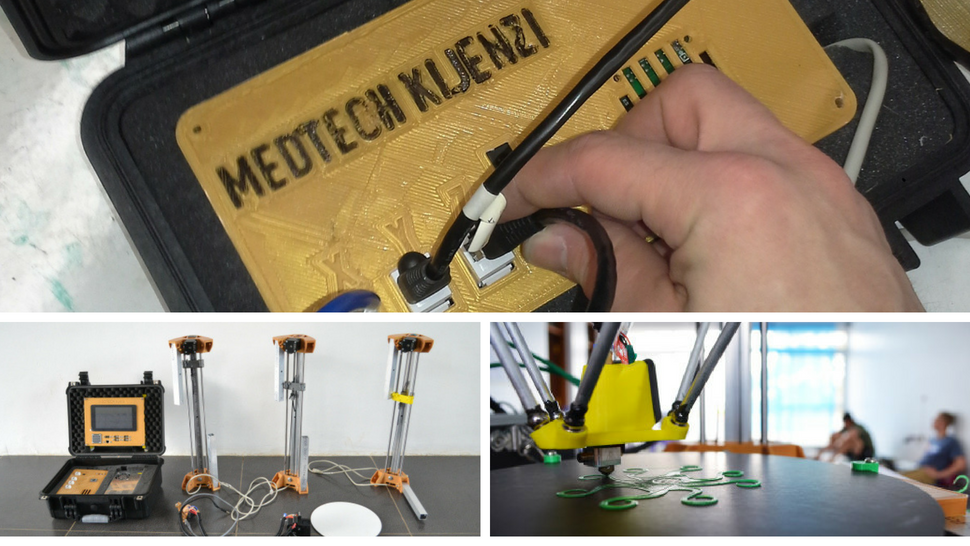

That?s where the Kijenzi (loosely meaning ?little maker? in Swahili) project-founded by Penn State doctoral student Benjamin Savonsen and professor John Gershenson-has stepped in to provide what might not have been possible a decade ago: quick and inexpensive 3D printing of medical devices and replacement parts.

Kijenzi is a unique venture: a project that sits at the intersection of engineering and social activism. The team, which includes a rotating cadre of Penn State students, enables East African entrepreneurs to print essential health care materials quickly, locally, and at a fraction of the cost of purchasing them.

Dream it, print it

?You?re taking a thick thread of plastic that?s on a spool, heating it and pushing it through a nozzle,? said Gershenson, explaining the 3D printing process. ?This nozzle is controlled by a computer that moves it in order to use this molten plastic, layer by layer, and build up whatever shape that you can dream up.?

Once set up with 3D printers in Kenya, it didn?t take long for the team to find ways to apply the technology. Savonen gave an example of how a small fix can have a huge impact. ?There?s a particular brand of microscopes used in the region, mostly used to screen for malaria. And on many of them, a basic, but essential, knob is notorious for breaking. Now, these microscopes are high quality. They can cost about $1,000 each, but they?re useless if that knob is broken.? The Kijenzi team was able to print a new knob for what amounts to pennies, suddenly rendering an expensive piece of equipment operational again.

The team has a number of similar anecdotes. Savonen said that many hospitals have quality machinery, which is often donated, but might not be operational. ?It?s not that it doesn?t work, but one little plastic part doesn?t work,? added Gershenson, ?which renders the rest of the technology nonfunctional.? A quick print of a piece can make an expensive piece of machinery usable again.

There is perhaps no more omnipresent medical instrument than the stethoscope. Every doctor uses one, but they are relatively expensive. Gershenson said that the part that commonly fails is the earpiece.

?A hospital came to us, and said, ?Here's the problem. We have all these stethoscopes that are sitting in a box because they?re missing ear pieces.?? After that meeting, a Kijenzi engineer went home that night, drew up a design that could be 3D printed, and completed a few test prints. ?We were able to show up the very next day with ear pieces,? said Gershenson. ?And we could print those for somewhere in the neighborhood of a penny a piece, in about 2 minutes each.?

Savonen also said that they recently consulted with an occupational therapy team on what kind of products their patients could benefit from, like wrist braces and hand-strengthening devices that can help patients regain strength in atrophied muscles.

Beyond replacement parts

According to Gershenson, the team is excited about about several upcoming initiatives, as well as the possibility of expanding Kijenzi?s work beyond Kenya. Next steps include collecting a wish list of items to be printed from hospitals they?ve worked with. ?Now that they really know the technology?s capabilities, we want to find out what they really want and need,? he said.

The next step is to dedicate an engineer and a 3D printer to a single hospital for several months, allowing them to quantify how much money they save the hospital and just how many instruments or pieces of machinery they can get up and running.

They?re looking beyond the hospital walls as well. Kijenzi is exploring the possibility of collaborating with local and national government institutions, in Kenya and beyond, with the goal of creating a curriculum to train local entrepreneurs on how to use 3D printers.

Engineers without borders

?We want to energize engineers around the world,? said Gershenson of the team?s lofty, but not unrealistic, goals. ?We want them to get excited to design these parts and getting the printable files online for hospitals to use… The beauty of engineering is, as long as you?ve got a laptop with [computer-aided design] software on it-wherever you are-you can have impact.

Kijenzi was originally founded by Gershenson and Savonen when they were at Michigan Technological University. In 2017, Savonen headed to Penn State to pursue his doctoral degree at the same time Gershenson came to lead the Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship (HESE) program.

Gershenson?s passion for the program is clear. ?If there are students who think, ?Wow, this idea of developing products and services for developing communities, and doing it with the purpose of trying to launch some sort of a social venture that can impact a million or more people?? ?If that?s exciting to them, Penn State HESE is the place to be. We?d love to hear from them.?