John Tolley, May 19, 2018

(Warning: If you?ve got a thing about eyes, then this probably isn?t the story for you. If the thought of people touching or getting anywhere near slimy, squishy eyeballs makes your constitution quiver, then turn back now, because ahead lies a tale of serious science, but one in which eyeballs play a starring role.)

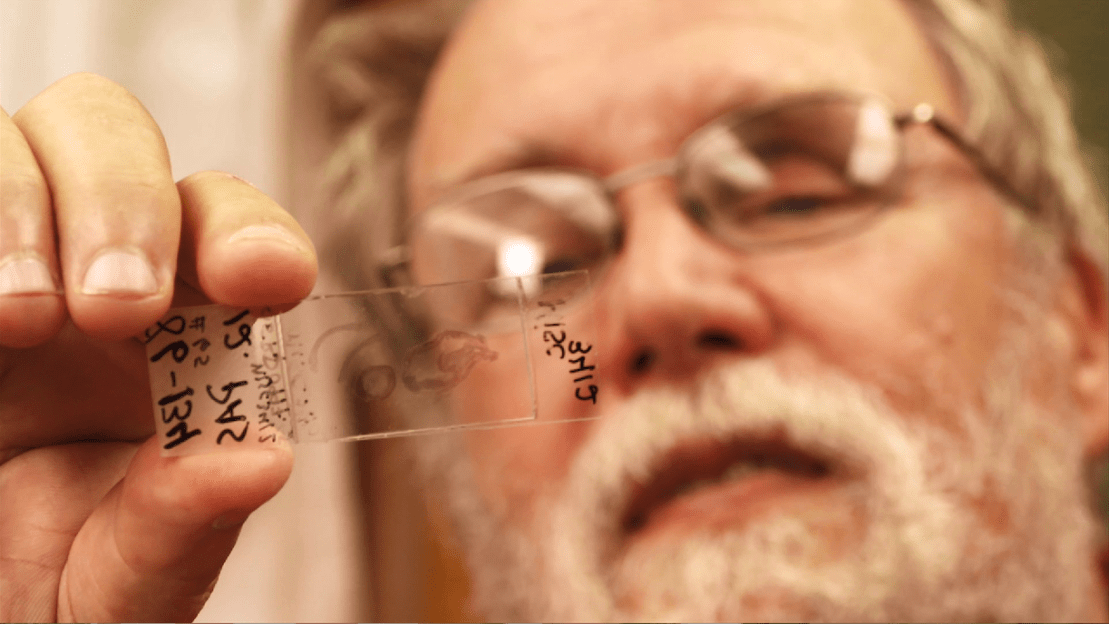

The University of Wisconsin-Madison is home to a lab with one of the most unique libraries of specimens in the world. The Comparative Ocular Pathology Laboratory of Wisconsin, or COPLOW, houses 58,000 different tissue slides, blocks and whole organs from the ocular system of a variety of animals. From rodents to rhinoceroses, these samples are sent in by veterinary ophthalmologists in order to diagnose a host of afflictions.

?Our clients often remove eyes or remove tissues from around the eye,? says Dr. Richard Dubielzig, COPLOW?s founder and a professor emeritus at Wisconsin. ?They want some confirmation of the disease process that?s happening. So, they will send it to us and we will make microscope slides out of it and examine it.?

The samples sent to the lab are most commonly from common house pets, such as dogs and cats, but they also receive tissue from horses, livestock and exotic zoo animals. One common example of an eye-related disorder that Dubielzig says COPLOW helps in diagnosing is a feline cancer called Diffuse Iris Melanoma (DIM.) While the cancer starts in the eye, it often metastasizes and can spread to the brain or to other vital organs and be fatal. After examining a number of tissue samples from cats with DIM, COPLOW pathologists have created an examination protocol to help veterinarians detect the cancer early and tailor treatment plans that can potentially preclude removal of the eye.

After they are used for diagnostic purposes, the samples are catalogued and stored for use by COPLOW in other areas. As Dr. Leandro Teixeira, the lab?s current director, explains, the slides are used as teaching aids, for research purposes and various other educational activities related to vision sciences.

?We have a very tight partnership [with our clients],? says Teixeira. ?They?re very interested in ocular pathology. We very often are on the phone with them exchanging information. They know about all of the research that happens in the lab. They?re very happy to send samples because they know that not only are they going to get a diagnostic report from very highly specialized pathologists, but they will be contributing to our research and our database.?

As the world?s largest lab specifically focused on veterinary ocular pathology, COPLOW?s extensive database is available to veterinarians and researchers around the world as a searchable library of tissue samples, slides and whole globes, the technical term for the eyeball. This allows for comparison and modeling of disease progression in animals. And, Teixeira notes that the work they do can be translated back to humans as many of the disease seen in cats and dogs a very similar to those that plague humans.

For Dubielzig, who has retired but still remains a volunteer consultant with the lab, a career studying a wide array of animal eyes is not without some fascinating stories, such as the time COPLOW researchers received tissue from two pythons that had deformed heads. Once the team analyzed the ocular tissue, they found that the deformities could be traced back to larval roundworms that had infected the snakes? eyes.

?We sent the tissues to a parasitologist who did genetic analysis and it turn out to be a species that hadn?t been identified before,? says Dubielzig. ?So, without my knowing it, they called it Serpentirhabdias dubielzigi, so now I have a worm that bears my name.?

Check out what's coming up next live on B1G+.

Check out what's coming up next live on B1G+.