John Tolley, May 5, 2018

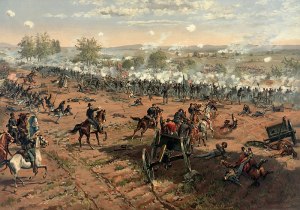

Musket balls and bullets sing as they hurtle through the low smoke and dust. Trees explode. Cavalry horses breathe hard, final breaths and collapse beneath their captains. Men do the same. All the while, a distant bugle and drum sound commands.

The haze of the battlefield takes a long while to lift. Sometimes it never does. For combatants, memories of how, when and why events transpired and who was where when can diverge wildly. But painting an accurate account of a particular battle is important for a number of reasons, chief among them the toll skirmishes take on the outcome of history.

That?s the prime motivator for Carol Reardon, the George Winfree Professor Emerita of American History at Penn State, who first visited the site of the Battle of Gettysburg when she was ten years old.

?There?s something about seeing the artillery on the ground,? explains Reardon. ?There?s something about thinking about what the soldiers here went through. There is something about just reflecting on the pain and the anguish, but also reflecting on the causes for which they were trying to fight. Modern America is what it is because of the things that happened here on this battlefield.?

Reardon had family on both sides of the battle. Her great-great-great uncles fought on Little Round Top. A southern ancestor laid down his life as part of the ill-fated maneuver known as Pickett?s Charge. The location fills her, she notes, with overwhelming sadness and awe at the events that transpired.

A leading authority on American military history, Reardon has dedicated herself to separating fact from fiction when it comes to war. It?s a herculean task. Generals inflate themselves to master tacticians. Some soldiers hand down tales of bravery, while others only wish to forget or, at least, spare their friends and loved ones the grisly details.

?What matters to [historians] more than anything else is the fact that we have a foundation of evidence to support what we say,? says Reardon. ?There are a lot of times we think we know what happened, but then we will find evidence that suggest perhaps our initial answer was too simplistic, sometimes outright wrong, but what we have to do is find the hard evidence.?

That hard evidence comes by way of thorough research, constant study and rigorous evaluation of a wide variety of source materials, from official accounts to the recollections of soldiers, witnesses and retellings of family lore.

Revisionism is often viewed by the general public as a verboten concept when it comes to history, admits Reardon. But all history is revisionist as scholars forever work to clarify our knowledge of past occurrences. ?Every time we find a new piece of evidence, a new insight, something that an eyewitness on the ground saw, it helps us understand that things are not usually black and white, that there are shades of grey, that there are nuances, that there are interpretations that perhaps the original interpretation never envisioned as being part of the story.?

To illustrate this point, Reardon points to Pickett?s Charge, the miscalculated Confederate offensive of which she is a scholar. No one will dispute the fact that Robert E. Lee pushed for the assault or that many of his subordinates saw the futility in it from the outset. But pour over the accounts of Virginians and South Carolinians fighting that day, and you?ll get a very different picture of who held the line and who acted the role of cowards. Differing accounts can also be found from companies hailing from various other rebel states, from Tennessee to Mississippi.

?Memory is an emotion-based force,? Reardon notes. ?It allows us to look at the past in ways that become comfortable for us. Those who approach the past using a memory-based perspective invariably become selective. They might sanitize the story, they might promote elements of it in a self-aggrandizing way. Battles are great for that because every soldier, when he thinks about it in years to come, wants to put his unit at the front of the lines.?

Although retired, Reardon continues her scholarship at Gettysburg. Recently she authored a guide to the site, one that adds new layers and reveals recently discovered accounts crucial to the current narrative. She is also instrumental in working with detachments of the ROTC?s 2nd Brigade, which covers the Mid-Atlantic and New England areas. For the officers-in-training, her work illuminates their staff rides: detailed walk-throughs of past engagements that inform their tactical studies.

?I look at it as a special honor and privilege to be able to bring a variety of individuals here to Gettysburg and share my favorite classroom with them,? remarks Reardon. ?Whether they be my Penn State students, officers from the United States military or international officers, these are the kind of circumstances that offer opportunities for today?s leaders to sit contemplate how they, someday, might have to respond to challenges that they face.?