Matthew Wood, November 17, 2017

Karthik Ramani has spent years finding ways to bring computer technologies closer to our fingertips — literally.

In doing so, the mechanical engineering professor at Purdue University hopes to find ways to make computers easier for us to use.

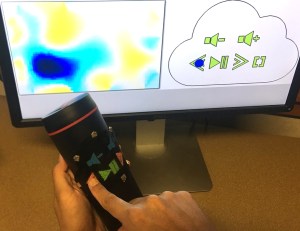

His team?s latest creation is a soft sensor for computing interactions, something it believes you can use just about anywhere. Called iSoft, the sensor is a thin, stretchable sheet with electrodes that works with low-cost sensors.

?One of the big motivations that drives my research and thinking is to make computing — the way we interact with computers — the best we can make it,? he says. ?The phone is a great example. Prior to that we sort of assumed [how] you interact with computers.?

That thinking helped produce the new device, which Ramani says can be used in the medical industry, in athletics or just about any other area where portable computing would be an advantage. But Ramani?s true innovation is in developing a technology that works when worn on the body.

Similar technology has already become available on the market. Levi?s and Google paired to create a ?commuter jacket? with gesture interactivity woven into the sleeve.

Ramani says his technology has them beat — and he even told them about it. He recently returned from California, where he gave a talk at Google headquarters in Mountain View.

?Now that we?ve patented our technology I can pull their legs a bit,? he recalls. ?I said, ?Look at this work Google is doing with Levi?s, they have to weave into thread. Ours is much easier.??

Ease is a goal for the Purdue team, as they try to make their products as user-friendly as possible.

?We want to provide interfaces so people want to (use the technology) and will do it,? Ramani says. ?We put buttons and switches for them to use.?

Though he makes it all sound simple, the research took years just to get to a point where the team was able to create a prototype. Now it requires more testing until the technology can be refined.

Tracking body motion and continuous contact have been barriers to previous products. One of the big keys was figuring out how to not only detect what the user is doing, but anticipate what the user was about to do.

?On the computing side, the biggest single barrier we broke through [was] when you move the finger, it doesn?t come back to the original shape immediately,? Ramani says. ?Touching and bending on these types of (softer) materials can be a challenge. We were able to do it in real time.?

The team recently submitted a paper to the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST). The next step will be figuring the best way to make the technology available to as many people as possible.

?I already have a lot of people asking if we can license the technology,? Ramani says. ?Their imaginations start opening up.?

Check out what's coming up on B1G+ and subscribe to watch for more live events.

Check out what's coming up on B1G+ and subscribe to watch for more live events.