John Tolley, November 11, 2017

It is hard for most us to imagine what life in the shadow of the Berlin Wall was like for citizens of Soviet-controlled East Berlin and NATO-aligned West Berlin. It divided not just a city, but families, communities, and, indeed, a whole nation. Although the wall completely encircled the democratic and free city of West Berlin, for the unlucky citizens of East Berlin it was a prison - complete with guard towers, anti-vehicle trenches and fakir beds lining its notorious ?death strip.?

The Berlin Wall?s dismantling, both symbolically and physically, began on November 9, 1989 as cheering crowds from the east and west hammered at its face with whatever implements they could find, a moment that heralded the eventual reunification of Germany a year later. Pieces of the wall can be found the world over, but in the US, the largest collection is held by the Newseum, a museum in Washington D.C. dedicated to promoting free expression the world over.

?There are 12 pieces of the actual Berlin Wall here,? explains Newseum chief technology officer Mitch Gelman. ?The wall divided east from west, brothers from sisters, freedom of expression from the confines of oppression. It helps the museum tell the story of freedom and how powerful freedom can be as a force that can right wrongs and bring people back together.?

Though, for all the powerful feelings and images conjured by the collection, curators at the Newseum felt that it did little to capture the experience of living in and with the Berlin Wall. So they reached out to the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS) to explore the feasibility of making their Berlin Wall exhibit come to life.

For Gelman, turning to UMIACS for help implementing Newseum?s goals was an obvious choice. The recipient of a sizable grant from pioneering virtual reality company Oculus, UMIACS is a leader in researching and exploring new media.

?What they did,? says Gelman, ?was brought to the museum the technology we needed in order to bring people to the streets of East berlin where they can experience the power of the Berlin Wall.?

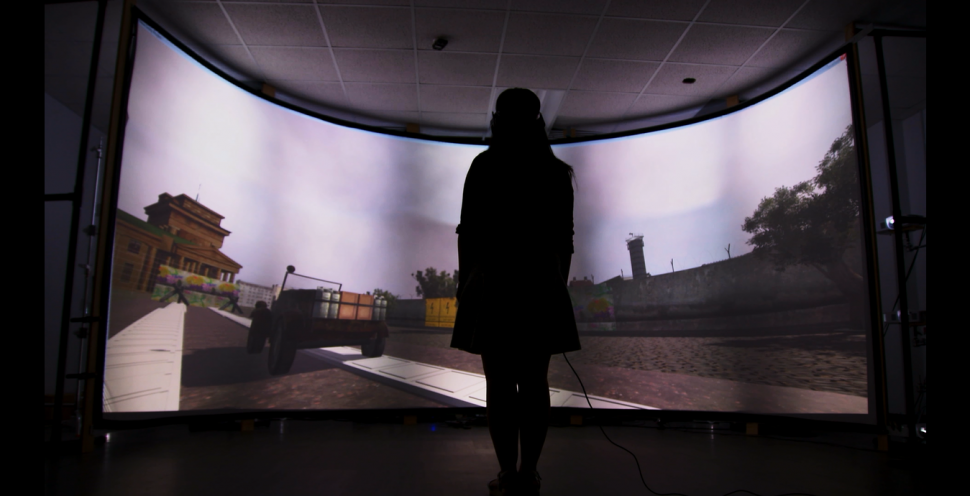

UMIACS developers used a video game design platform called Unity to create a proof-of-concept for the Newseum?s ultimate vision. In three dimensions, the team modeled an environment that allows users to walk the streets of East Berlin, view both sides of the city from atop the guard tower and even take part in the wall?s dismantling.

Working with archivists at the museum, developers, such as Mukul Agarwal, a graduate student in human-computer interaction at Maryland?s Information School, were able to seamlessly integrate visual assets into the environment, making it all the more authentic.

?It was really a great opportunity,? notes Agarwal. ?We had to keep in mind that this is a huge production and it is going to be seen by [around] a million people a year, so we had to keep in mind the small things and do it really well.?

For UMIACs director Amitabh Varshney, working with the Newseum was a chance to not only test their mettle, but to advance the way education is delivered.

?We are toolmakers for a variety of disciplines. We are proudest when users of our tools come to us and say, ?We would like to work with you to devise the next generation of tools for teaching, learning and communications?. With an amazing team of students and scientists, we are able to serve society in a way that makes a meaningful difference in everyone?s lives.?