John Tolley, March 25, 2017

In case the name isn?t clear, nanoparticles are small. How small?

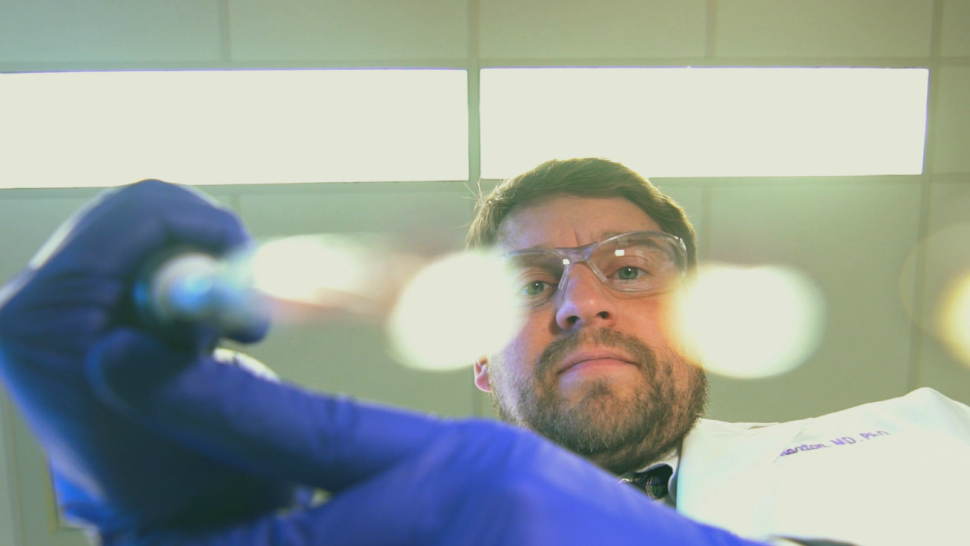

?A dime is about one millimeter thick,? explains Northwestern University researcher C. Shad Thaxton, M.D. Ph.D. ?If you take a dime and slice it a thousand times, you end up with a thousand one micron thick pieces of dime. If you take one of them and then slice it a thousand more times, those are one nanometer thick.?

But, for what nanoparticles lack in size, they more than make up for in potential, says Thaxton, whose work focuses on the use of nanoparticles in medical applications.

A recent, and fortuitous, discovery by the Feinberg School of Medicine associate professor may soon have a major impact on the treatment of certain types of B cell cancer, such as lymphoma and leukemia.

Thaxton and his team were originally looking into the role nanoparticles might play in cardiovascular disease therapies, particularly as they relate to cholesterol metabolism, but soon realized the farther reaching implications of their findings.

?We began applying these same materials to cancer. We found that some cancer cells have a tremendous need for cholesterol,? explains Thaxton. ?These nanoparticles that we make in the laboratory are able to bind to these cells and inhibit them from taking up cholesterol. That very simple mechanism is very potent at killing cancer cells.?

It was another stroke of good fortune that brought Thaxton to study nanoparticles in the first place. On a study break while still a student at Feinberg, he picked up a copy of Scientific American. In it was an article profiling the work of Chad Mirkin, who was researching nanotechnology in his lab on Northwestern?s main campus.

Thaxton knew what he had to do. ?Me being here at Northwestern and Chad Mirkin being here at Northwestern, I said, ?Well, I have to contact him to see if I can get involved in this really interesting field.??

Initially hesitant to let a medical student with a biology background into his chemistry lab, Mirkin eventually warmed to Thaxton. They soon found that their respective areas of expertise could be complementary to one another. While Mirkin and his research chemists were busy studying the structure of nanoparticles and how to build them, Thaxton?s portion of the lab could work towards practical medical applications for them.

According to Thaxton, the relationship afforded him a greater scope in terms of the what he could accomplish.

?The neat part about being able to synthesize something from the bottom up is that you can begin to tailor the properties,? he says. ?If we change the chemistry just a little bit, we may be able to impart new functions that may, in fact, drive new therapies.?

Today, Thaxton, who serves as a resident of Northwestern?s Simpson Querrey Institute for Bionanotechnology, is the director of his own lab located steps from the university?s hospital in downtown Chicago. It?s a location that he says brings a certain salience to his work.

?I always think about getting [our work] across the street. We?re working on technologies that we want to get across the street, into the hospital.?