Matthew Wood, December 12, 2016

When it comes to the power of LEDs, a group of researchers at Ohio State University is helping us to see the light.

The team is working on ways to develop foil-based, light-emitting diodes for portable ultraviolet lights. Already used by military and humanitarian organizations to help purify water and sterilize medical equipment, the discoveries by the OSU team would make these devices much smaller and more portable.

?The commonly used technology for UV light is mercury lamps,? explains materials science doctoral student Brelon May. ?Those are large and contain mercury. So if you break something, you?ve infected everything again.?

May has been working on the project at OSU for the past three years. He and Roberto Myers, associate professor of materials science and engineering, recently had their results published in the journal Applied Physics Letters.

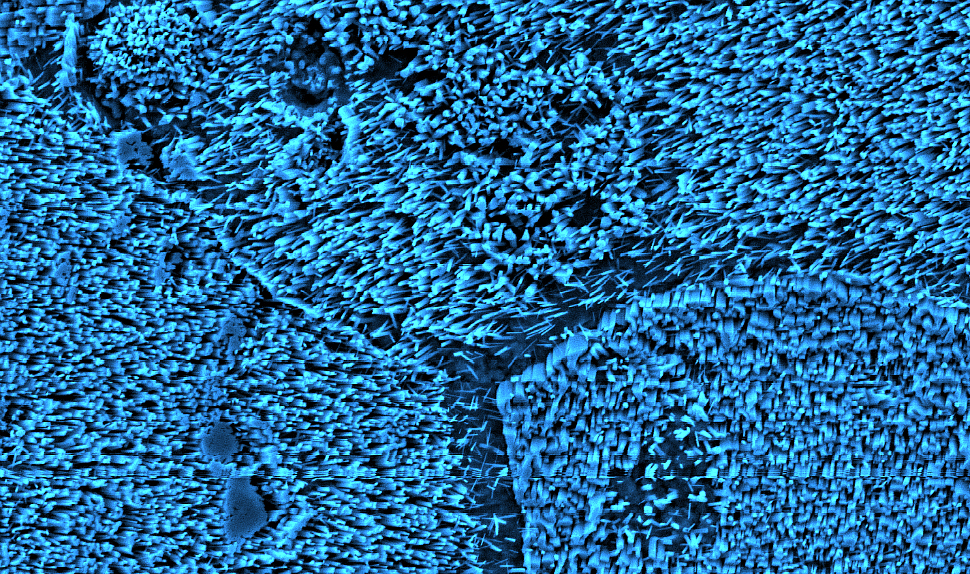

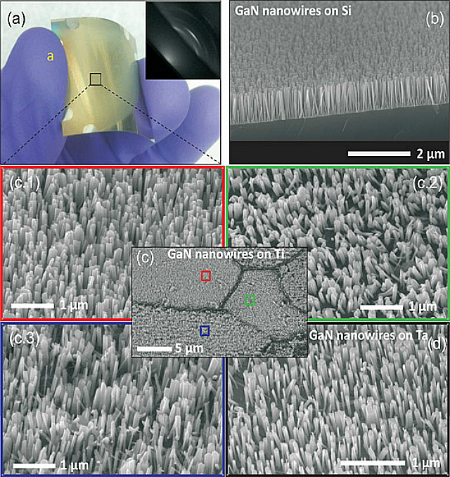

Part of the problem was the process used to grow nanowires to create the light is arduous and expensive. The OSU team found a way to grow these nanowires on much cheaper and more abundant surfaces like aluminum. That means they can grow a lot more in a shorter amount of time.

?Once we saw we could grow on these thin metal films, I said, ?Why don?t we grow on these bulk flexible foil??? May says. ?Now you lay down a sheet and you have a significantly larger surface area. They don?t have to be a higher quality of wires. The big thing about this is since it?s on untreated metal foil that are also flexible, it opens the door to roll-to-roll fabrication.?

The original project was funded by the U.S. Army, which wanted the group to look at developing ultraviolet lasers. While the subsequent research may provide better humanitarian services — such as purifying water, detecting biological agents and treating contaminated equipment — May warns that the research is just in its infant stage.

?We didn?t invent a new way to purify water. We kind of opened the door for a new manufacturing technique that could show the world how to manufacture LEDS in a much easier way,? he says. ?Mercury lamps have been around 140 years. We?ve been researching this for 20 years. In 120 years, we should be better than them at least. It will happen. I think it will happen in our lifetime. But research happens slowly and you have to make sure you do it right.?

The next step is to develop a machine to handle high output of these nanowires. The group submitted a grant in October to help with the funding in a collaboration between their department and the OSU Center for Continuing Medical Education.

?Once you develop a prototype for this machine, that really opens the door for industrial production,? May says. ?We have a lot of experience with it. It?s really just building off of existing technology. We?re just merging the technology in ways that haven?t been done.?

See what's coming up live on B1G+ every day of the season at BigTenPlus.com.

See what's coming up live on B1G+ every day of the season at BigTenPlus.com.