Courtney Jacquin, September 10, 2016

Over the past few years, hundreds of cities across the U.S. have instituted bans on lightweight plastic bags. Chicago?s ban started Aug. 1, 2015 and Minneapolis?s will begin in June 2017. A statewide plastic bag ban is on the California ballot in November.

The reason for these bans is because the lightweight bags? non-biodegradable materials are harmful for the environment. But could plastic bags, and other common plastic materials, be made sustainable?

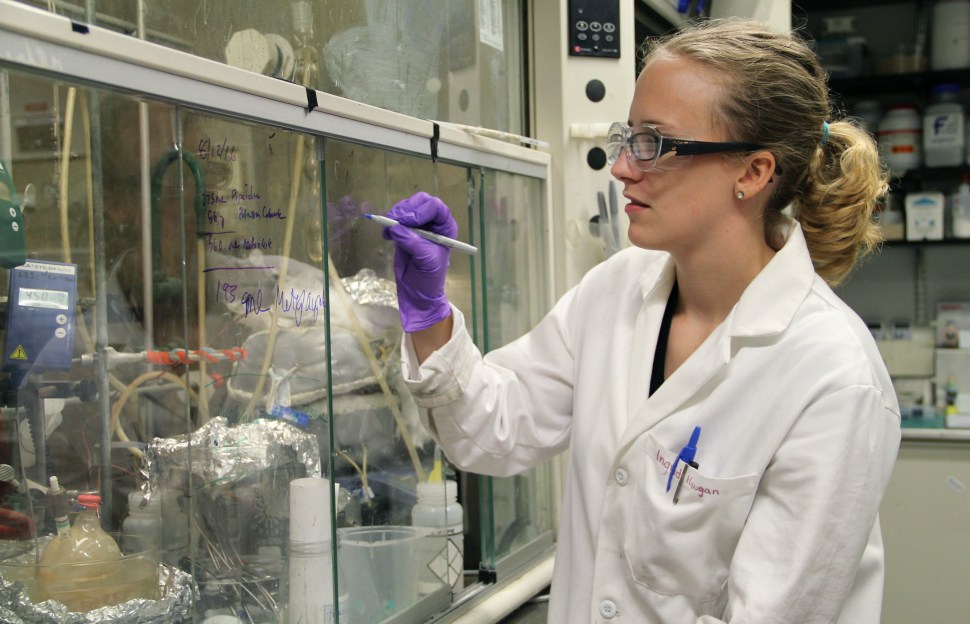

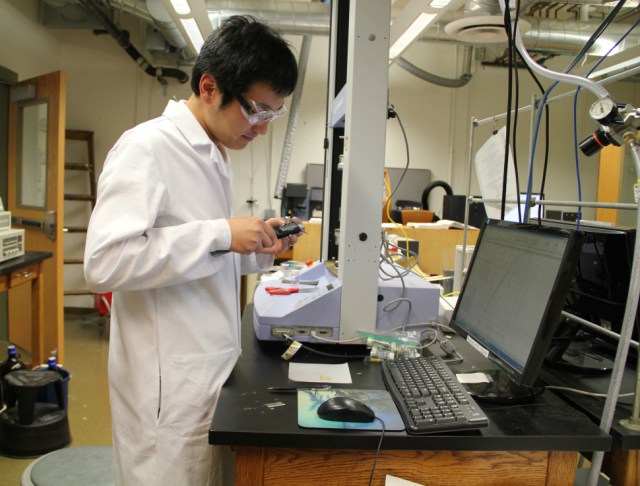

That?s exactly what Director Marc Hillmyer and the Center for Sustainable Polymers at the University of Minnesota is trying to accomplish.

?Plastic is ubiquitous, it?s everywhere, but the vast majority of plastic comes from nonrenewable resources like oil and natural gas and they persist in the environment when not disposed of properly,? Hillmyer says. ?Our center works on not only how we can change the origin ? but how can we design materials that are not harmful or [don?t] accumulate in the environment.?

The Center for Sustainable Polymers at the University of Minnesota is a National Science Foundation-funded research center. It focuses on sustainability issues through the science and technology of polymer research, education and public outreach. Hillmyer has been the director of the center since its creation in 2009.

One example of the biodegradable materials the center is optimistic about is PLA, or polylactide, a polymer (the molecule in plastics) that comes from corn and is completely compostable. Currently, the University of Minnesota is utilizing this material in its dining halls in its cups, cutlery and food storage packaging, a major leap forward in the broader adoption of sustainable polymers.

Another major recent development for the Center was generating a material made from sugar that can be used in polyurethane. Polyurethane foam is the material typically found in seat cushions and bedding.

?We re-engineered ? a bacteria such that they ate sugar and excreted a molecule that we could turn into this polyurethane precursor,? Hillmyer said. ?So we use that molecule to make polyurethane foams, and you could not tell the difference between the foams we made and the foams that are commercially viable.?

Hillmyer noted some materials that come from petroleum can be biodegradable and some from plant materials are not biodegradable. For a plastic to be biodegradable, it does not necessarily need to be made from plant-based organic matter.

?Obviously the win-win situation is coming from biomass and ultimately being able to be degraded, but it?s a bit of a common misconception,? he said.

The Center has also developed compost bags for the City of Minneapolis: biodegradable bags for the composting bins in the homes of Minneapolis residents, which are options for waste disposal beyond garbage or recycling bins.

Apart from developing these biodegradable solutions, a major goal for Hillmyer and the Center is providing materials that are affordable and can compete against traditional plastic products.

?What we're trying to always keep our mind on is to try to do these transformations and these manipulations and generation of new materials in an economic manner,? Hillmyer said. ?Because when you talk about commodity materials like plastics, these are inexpensive materials to compete in the marketplace. You've got to make economic sense. Nobody is going to buy a plastic bag that costs $5.?

Basketball is back! Find available live games on our B1G+ app via BigTenPlus.com.

Basketball is back! Find available live games on our B1G+ app via BigTenPlus.com.