John Tolley, August 11, 2016

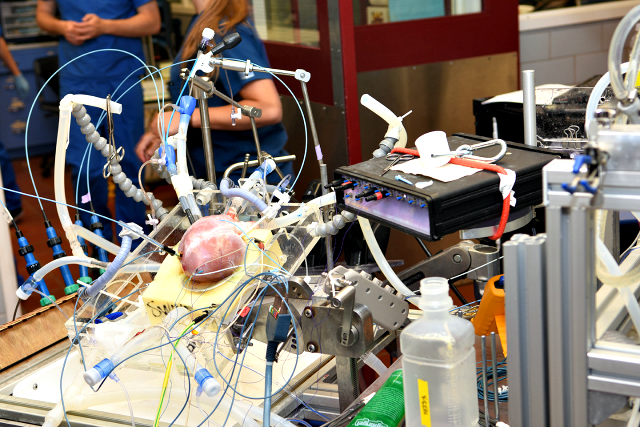

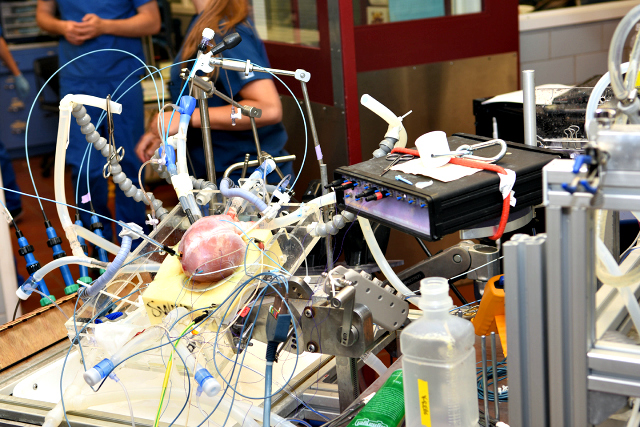

Most people would say watching a disembodied pig heart go from pallid and inert to undulating with the rhythm of life would be distinctly out of the ordinary.

But most people don?t work in the University of Minnesota?s Visible Heart Lab where it?s just called Tuesday.

Since 1997, Paul Iaizzo, PhD, the lab?s founder and principal investigator, has been working with a team of researchers and students to reanimate animal hearts as a way to closely study the organ in operation.

?It was actually started in collaboration with Medtronic,? recalls Iaizzo, who is also a professor of surgery, integrative biology and physiology at the university. The team's partnership with Medtronic is the largest private-academic collaboration they have due, in part, to Minnesota's long association with the medical community.

The team started off small by reanimating guinea pig hearts, but a representative of the medical device firm spurred them on to bigger specimens due to the ease of study. "We had their engineers come and see what we were doing and they said, ?That?s cool, but it?d be really helpful if you could do that on a large mammalian heart.??

Within a few months, the team reanimated its first pig heart. To further explore the specimen, Iaizzo placed a laryngoscope inside of the beating heart, which allowed him to see all of the valves as they opened and closed. Fascinated by this unique perspective, they were soon using videoscopes to fully document the fully functional cardiac anatomy.

Building upon their early successes, the team was able to secure a human heart for study in 1999 - one deemed not viable for transplant. Since then, they?ve reanimated 70 human specimens.

?On the rare occasion [when] the heart is deemed not viable, we get it to the lab within four to six hours,? explains Iaizzo. ?The first thing we will try to do, for the first two hours, is collect all the educational images we can. Those are put online in a free access website called the Atlas of Human Cardiac Anatomy.?

The Atlas is used worldwide to teach human cardiac anatomy. After serving 500,000 users in the last year alone, The Atlas is now being translated into multiple languages.

Supplementing the Atlas is the lab?s Human Heart Library, which contains more than 400 preserved specimens for use by the university?s medical students and the several hundred biomedical engineering students that flock to the University of Minnesota and the Twin Cities? high density of medical device companies.

According to Iaizzo, it was Dale Wahlstrom, a former medical device industry advocate and past president of Minnesota?s Medical Alley Association, who suggested the need for the library.

?He said that people in his industry, especially those working on cardiac devices, they build these devices, but they?ve never had a chance to see a human heart [in operation],? says Iaizzo.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BoN0OiKpuJQ

Now, Iaizzo and his team are offering an even more detailed look, using MRI and CT scan technology to create DICOM 3D images of more than 260 of the hearts in the library. With a bank of eleven 3D printers in the lab, the team is able to turn 3D images into physical models.

?We had a summer academy of undergrads, and we gave them each a [3D printed] heart specimen,? Iaizzo says. ?They took three hours to paint all the different anatomy within it. Taking the time to paint all of the internal anatomy really puts it in your brain in a unique way.?

The 3D printers are also used for a program called Care Prints, which offers doctors and patients a unique, pre-surgical view of the patient?s heart.

?We?ll print out the whole heart, or the blood volumes, and we can do it [four to five times enlarged] for them,? explain Iaizzo. ?The surgeons can then discuss [procedures] with their care team. Or, they can show the patient and the family.?

One of the hallmarks of the lab, says Iaizzo, is the open atmosphere that it fosters. Unlike many high-level research labs that operate in seclusion, the Visible Heart lab is dedicated to showcasing the advances in medical knowledge going on within their walls.

?We have several thousand people visit the lab on an annual basis,? notes Iaizzo. ?All of our undergrad biomedical engineering students and medical students will tour through [it]. We even have local high school groups come in for a whole day in the lab. We really have a huge mission for outreach education.?

See what's coming up live on B1G+ every day of the season at BigTenPlus.com.

See what's coming up live on B1G+ every day of the season at BigTenPlus.com.