Matthew Wood, July 14, 2016

In his nearly 40 years as a professor of astronomy and physics at the University of Minnesota, Lawrence Rudnick has made countless discoveries. Yet for his latest project, he needed a little help from some new friends thousands of miles away.

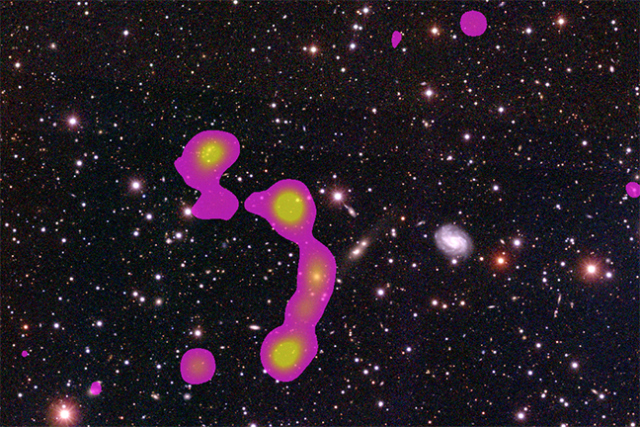

Rudnick followed up on the work of a pair of Russian ?citizen scientists? to help produce a paper on the discovery of a rare galaxy cluster 1.2 billion light years away. It?s the latest use of volunteers to help ignite discoveries in the cosmos, something Rudnick says is invaluable for him and colleagues.

"They discovered that this little patch was part a giant structure, much larger than we had showed them,? says Rudnick.

Their discovery is called a wide-angle tail radio galaxy, one of the largest ever found and part of a previously unreported galaxy cluster. The pair were given co-author status in a paper published in the Oxford Journal?s Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. They were even immortalized in the galaxy?s name: the Matorny-Terentev Cluster RGZ-CL J0823.2+0333.

The two modern-day Galileos - Ivan Terentev and Tim Matorny - are both astronomy enthusiasts who are part of a web-based group called the Radio Galaxy Zoo project.

The Radio Galaxy Zoo project, which utilizes the University of Minnesota-based volunteer research platform Zooniverse, is reliant on the crowdsourcing capabilities of a large number people working together on big projects.

?What [Terentev and Matorny] did independently of one another is they said, ?These patches look suspicious. This can?t be the whole story,?? Rudnick says. ?I was just looking around at various comments people were posting and said, ?Oh my god, they actually have found something.? This is very difficult to do on a computer, so we knew having a lot of eyes on it would be enormous help.?

For Julie Banfield, a researcher at the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO) in Australia, who took over much of the research after the initial discovery and was credited as lead author of the research paper, it was quite a surprise to see the results of the citizen scientists? work.

?I was blown away by the discovery,? she says. ?This is a fantastic example of how citizen science projects contribute to our knowledge of the Universe. It empowers people to contribute to scientific discovery. This discovery illustrates that the Universe is a vast place and we have yet to unlock all the secrets.?

These citizen scientists come from all over the world, tracking tens of thousands of celestial images and determining which could be of use for further exploration.

?They?re what we call super users,? Rudnick says of Terentev and Matorny. ?We have a lot of people who come in and classify a handful of [images] and they?re done. Others do tens of thousands of [images]. These are those guys.?

For Terentev, it?s just another notch on his astronomical belt, having co-authored three other papers from findings he made with another citizen science group. He said this ranks up there with some of his greatest achievements.

?I was amazed,? he says. ?I always wanted to be part of something like that. It was like a dream come true for me. It?s very exciting because it is a result which you can actually see and show somebody. It?s also encouraging because this shows that something like this is possible for an amateur.?

So just how adept are these amateur star gazers?

?If it?s an object in one out of 10,000 images, these guys will find it,? Rudnick says.

While the Radio Galaxy Zoo project isn?t necessarily a formal University of Minnesota project, it has Golden Gopher prints all over it. Rudnick said he brought a number of professors and grad students in to help verify the discovery and move it forward.

?There are a bunch of us here who have joined in on the project,? Rudnick says. ?We definitely have a Minnesota presence.?

As for the future of citizen scientists contributing to astronomical discoveries through Minnesota and elsewhere, Rudnick says the sky is - literally - the limit.

"I hope to increase recognition that the citizen scientist projects provide,? he says. ?Doing this kind of crowdsourcing can give us valuable information. In doing this, people can pick out oddities that a computer would never have picked out."

By Matthew Wood

See what's coming up live on B1G+ every day of the season at BigTenPlus.com.

See what's coming up live on B1G+ every day of the season at BigTenPlus.com.