BTN.com staff, July 25, 2015

The human experience of slavery in the United States was recently and memorably captured in the Oscar-winning Best Film ?12 Years a Slave,? adapted from the 1853 novel of the same name by Solomon Northup. But while Northup?s long fight to reclaim his freedom after a ruthless kidnapping was an undeniably compelling story, it wasn?t representative of the typical struggle of African-Americans who sought to break the bonds of slavery.

?It?s not ?12 Years a Slave,? but ?100 Years a Slave Family,?? said Nebraska history professor Will Thomas. ?It took that long in many of these cases.?

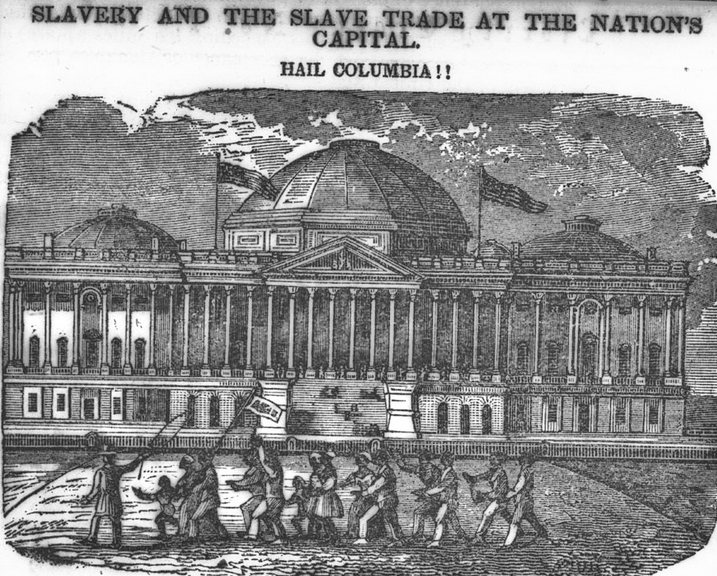

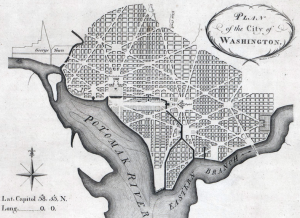

?These cases? are the hundreds of lawsuits filed in Washington, D.C., by African-Americans seeking freedom in the decades that followed the American Revolution. In a joint research effort by the University of Nebraska and University of Maryland, historians recently uncovered court documents that strongly suggest our understanding of slavery - informed by both historical research and fictionalized accounts - is hardly the whole story.

?These cases? are the hundreds of lawsuits filed in Washington, D.C., by African-Americans seeking freedom in the decades that followed the American Revolution. In a joint research effort by the University of Nebraska and University of Maryland, historians recently uncovered court documents that strongly suggest our understanding of slavery - informed by both historical research and fictionalized accounts - is hardly the whole story.

?Across those cases, thousands of individuals are named, maybe 5,000 to 6,000 names, and probably tens of thousands of relationships [are] embedded in these cases,? Thomas said. ?These cases help us understand slavery in multiple dimensions. Probably the most important is that we often think of resistance to slavery as escape, running away. But these cases show a completely different approach or strategy, which is more of a long-haul approach.

?They are not famous or published like Northup,? he added, ?yet we?re able to cross-reference these documents with other documents like plantation records, church records and county records and, in many cases, verify and confirm their claims. It?s astonishing the quests these families undertook.?

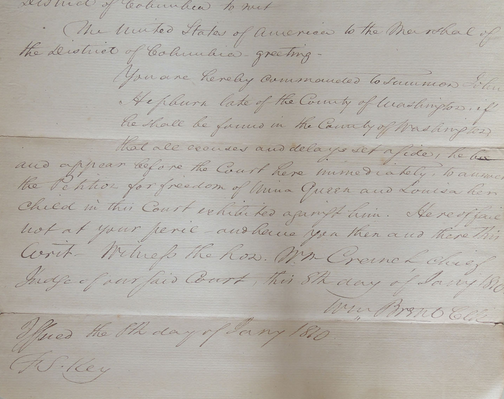

The ?O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law and Family Project? is revealing some previously underreported and, in plenty of instances, misreported facts about slaves, their families, slaveholders, abolitionists and the legal system during that time. The legal documents they?ve found that make up the basis of their work were filed from 1800 up until 1862 - the year before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

One of the more interesting names found in the documents is Francis Scott Key, best-known for writing the National Anthem, ?The Star-Spangled Banner.? Key was slaveholder who also happened to be lawyer, and he represented both slaveholders and petitioners attempting to gain freedom through legal means. In a way, he represents the ambivalent views of slavery held by the entire country in the years before the Civil War.

?He?s motivated by the ideals of the American Revolution and Enlightenment,? Thomas said of Key. ?He opposes the international slave trade, but his reform only goes so far. He?s certainly not an abolitionist. He?s trying to square slavery with all these values he has and he?s trying to free slaves, but he?s not entirely opposed to slavery.?

The collaborative project between Nebraska?s Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities is seeking to digitize some 500 cases in their original form at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C. Thomas said the project, funded by a two-year grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, is a little more than halfway complete with 285 cases now in digital form.

Thomas said the researchers are encoding the relationships among all parties so that scholars, teachers and students are better able to track information and develop new scholarship based on what they find. The digitized documents should be available to the public by March of 2016, he added.

[btn-post-package]But even though that process isn?t complete, the researchers have already gleaned a number of insights. For instance, enslaved petitioners who sought to gain their freedom through the court system found the going tough and were often unsuccessful, according to Thomas.

?It was multi-generational and the resistance strategies were complex, local and familial,? he explained. ?One of the things that strike me about these petitioners for freedom is that they stay in Washington, D.C., [or] Prince George?s County [in Maryland] for years and decades. They resist slavery through legal means, family and kinship. And they stay in place. It?s a fascinating, important story that?s not understood.?

By Tony Moton