BTN.com staff, BTN.com staff, June 27, 2015

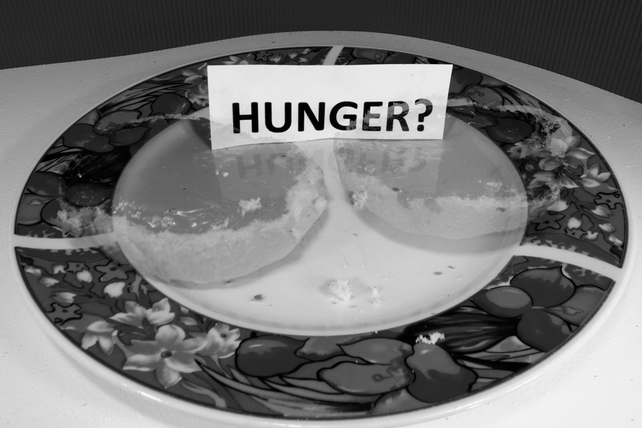

When broaching the sensitive subject of healthy eating and body weight with their children, parents often feel like they?re biting off more than they can chew.

To explore this subject further, a team from the University of Minnesota published a study that examines how parents talk to their adolescent children about eating and weight, and how that differs based on a household?s status as food-secure or -insecure. And that, in turn, can have some interesting downstream effects on people?s health throughout their lives.

?It isn?t always easy for parents to know what to do or say,? said Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, a University of Minnesota professor of epidemiology and community health. ?There is a lot of misinformation out there.?

?Food security? describes a household in which all people have access to sufficient, safe, nutritious food at all times, thereby enabling them to maintain a healthy and active lifestyle. However, that doesn?t mean that they always do. If a home has abundant food but the family doesn?t prioritize physical activity, it can lead to lifelong battles with obesity and related health problems.

At the other end of the spectrum, there?s a different set of struggles. In food-insecure homes, very young children are often fed first, as there is more concern about their growth and malnourishment. But what happens to these kids when they grow into adolescence? As it turns out, many of these teenagers are forced to ?grow up faster? in these families, because they?re viewed as old enough to either go without or somehow find their own food outside of the house.

Additionally, the university?s research indicated that parents in food-insecure homes were more likely to restrict eating overall, encourage dieting and make comments on their adolescent child?s weight compared to those from food-secure homes. Also, low-nutrient foods are generally more available and much cheaper than healthier options, which can instill poor eating habits in kids that extend well into adulthood.

Additionally, the university?s research indicated that parents in food-insecure homes were more likely to restrict eating overall, encourage dieting and make comments on their adolescent child?s weight compared to those from food-secure homes. Also, low-nutrient foods are generally more available and much cheaper than healthier options, which can instill poor eating habits in kids that extend well into adulthood.

The study?s lead author - Katherine Bauer, who received her doctorate in epidemiology from the University of Minnesota - said her experiences as both a researcher and a parent spurred her to ask whether parents in food-insecure homes deal with their adolescents differently than those in secure ones.

?It's hard to give [food-insecure parents] messages like, ?You should talk to your kid this way,? or, ?You should do this with your family,?? she said. ?It?s ignoring that they have very good reasons for doing what they do. Some [things] you do knowing what?s good and bad, what will have a better outcome. But sometimes you parent a certain way because you're really tired, or you don't have enough money to buy the kinds of food you want.?

It will be a challenge for public health officials to educate parents in a way that acknowledges their position, she added. Also, most existing programs that give them information about nutrition, such as those through WIC or Head Start, tend to focus on infants and young children.

Bauer?s hope is that the research being performed by her and her colleagues will help turn some attention to the nutritional needs of adolescents. She?s confident this will change based on encouraging feedback from a nine-week parenting course she held in West Philadelphia that addressed weight-related eating and family strategies, as well as broader advice on raising pre-teen children.

?At the very least, moms might be more receptive to these messages because they'd feel, ?OK someone gets my circumstance and sees that I'm making smart decisions given my context,?? Bauer said.

By Betsy Piland