BTN.com staff, June 4, 2015

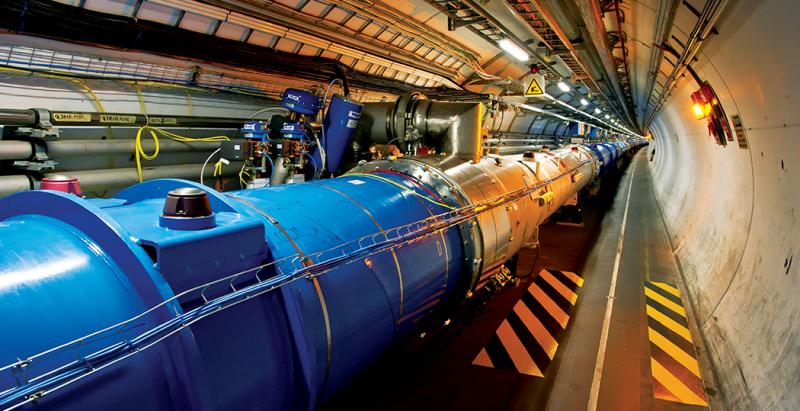

It?s not hyperbole to say that the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is gargantuan. For one thing, it?s the world?s largest machine, supported by the world?s largest computing grid. And the ?centerpiece? of the LHC is a ring tunnel beneath the Franco-Swiss border that measures 17 miles in circumference and goes more than 500 feet below the surface in places.

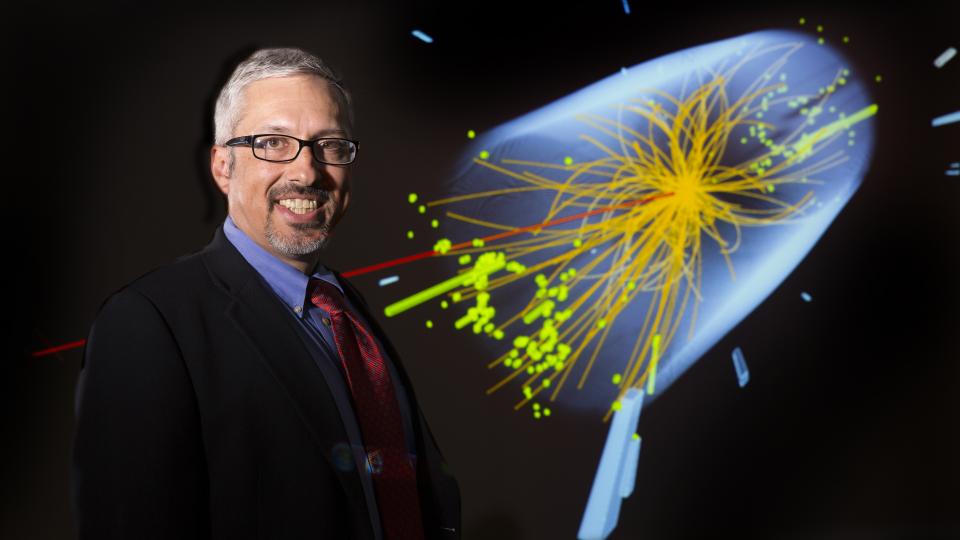

Constructed near Geneva, Switzerland, by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the particle collider took a decade to build before becoming operational in 2008. And Aaron Dominguez, associate dean for research and global engagement and a full professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Nebraska, is on a team of scientists that not only helped design the LHC, but also continues to assist in its maintenance.

Constructed near Geneva, Switzerland, by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the particle collider took a decade to build before becoming operational in 2008. And Aaron Dominguez, associate dean for research and global engagement and a full professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Nebraska, is on a team of scientists that not only helped design the LHC, but also continues to assist in its maintenance.

So, how does it work? Essentially, the LHC accelerates protons in the tunnel to a velocity approaching the speed of light, then smashes them together in experiments approximating an atomic game of marbles. The resulting collisions enable scientists to study the smallest structures of the universe and, perhaps, discover the how and why of our existence.

?We are trying to answer some of the fundamental questions people always ask,? Dominguez said during a telephone interview from Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. ?It leads back to the creation of the entire universe, and I?m damn lucky to be in a place to be able to answer some of those questions. Pretty excited.?

Dominguez was at Cornell to attend a meeting of U.S. scientists involved with an LHC experiment. He went there in late May to convene with colleagues involved with the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) experiment, a sizable particle physics detector that Dominguez helped fine-tune at the LHC.

?[The detector] can image the paths of the charged particles that come from the collision of the protons,? Dominguez explained. ?It?s like a super-fast digital camera that can take [pictures] 40 million times a second and run for a year.?

Dominguez, who grew up in Albuquerque, N.M., knew from an early age that he wanted to pursue a career in science, but his interest in particle physics specifically wasn?t sparked until he was an undergraduate at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena - known to many as the setting of TV?s popular ?Big Bang Theory.?

Dominguez described his Caltech days as a ?boot camp for scientists,? although he did find time to participate in track and field and cross country and even made it to national levels of competition at the Division III school.

?I definitely learned a lot of physics and how to be a scientist at Caltech, but I?m a more well-rounded person for the [athletic] activities,? he said.

Dominguez said he was swayed by Nebraska professors Greg Snow and Dan Claes to get involved with the CMS experiment. The pair had been involved in the conceptual phase of the project for years before it became a reality at CERN.

Since arriving at the University of Nebraska in 2004, Dominguez has logged plenty of air miles traveling to Switzerland to work on the CMS experiment. In all, he estimates his work has taken him over there for about a total of three of the last 11 years. And even when he isn?t there, he?s there.

?We do lots of stuff remotely, videoconferencing on a daily basis,? he said. ?But there?s nothing like being in the same room with people and having your hands on the equipment. There are times you have to be there.?

Dominguez and his fellow Nebraska physicists are currently leading an $11.5 million, eight-university effort to upgrade the CMS. The LHC itself was just recently started up after a two-year shutdown for maintenance and repair. However, before that hiatus, the collider and the CMS were credited with enabling scientists to observe the existence of the Higgs boson, a class of particle named after physicist Peter Higgs.

?It was darn hard to find,? Dominguez said of Higgs boson. ?It took us nearly 40 years to find it, and we were looking constantly.?

[btn-post-package]On July 4, 2012, CERN reported that the CMS experiment was one of the two tests at the LHC that confirmed the observation of the Higgs boson. A little more than a year later, Higgs and Francois Englert were awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in physics ?for the theoretical discovery of a mechanism that contributes to our understanding or the origin of mass of subatomic particles.?

?I was very happy to see Higgs and Englert get the Nobel Prize in Physics,? Dominguez said. ?It was extremely gratifying and humbling to know that the work of me and my many colleagues led directly to this.?

By Tony Moton