BTN.com staff, BTN.com staff, May 3, 2015

It?s a genre of music invented by former African slaves and their descendants just a few decades after emancipation. Though novel, the rhythms and melodies were the result of a fusion between the native musical forms they brought over from their home continent and instrumentation they encountered in their new country. As it evolved and grew more popular, it became an emblem of national pride, unity and ingenuity.

We?re talking, of course, about Brazilian samba.

Americans can be forgiven for assuming the description above referred to jazz or blues. After all, that?s their frame of reference, and the history of those kinds of music unfolded in much the same way. But as University of Illinois history professor Marc Hertzman points out, the story of samba is paradoxically similar to and different from those genres.

Americans can be forgiven for assuming the description above referred to jazz or blues. After all, that?s their frame of reference, and the history of those kinds of music unfolded in much the same way. But as University of Illinois history professor Marc Hertzman points out, the story of samba is paradoxically similar to and different from those genres.

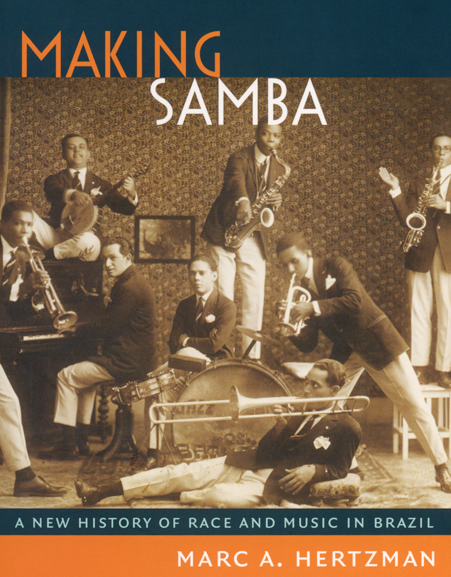

Hertzman wrote about its role in shaping cultural and political change in his recently published book, Making Samba. The book explores the intersections of an emerging creative class, the music business in Brazil and cultural acceptance - all against a backdrop of simmering tensions spurred by race, politics and what did or did not count as ?authentic? samba. It also demonstrates the crucial role music can play in bringing people of all backgrounds together, overcoming fear, antagonism and injustice.

The history officially begins less than three decades after the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888 - the country was the last one in the Western Hemisphere to end it - when a young Afro-Brazilian named Donga registered a samba song called ?Pelo Telefone? with the National Library in Rio de Janeiro in 1916.

Interest in samba skyrocketed in Brazil (and beyond) soon after that, and it eventually became as much a symbol of Brazil as the Christ the Redeemer statue, Carnival parades and Copacabana beach. That surge in popularity and prestige brought new opportunities and respect to people who just a few decades before were utterly disenfranchised.

?The rise of samba accompanied, and in some ways helped propel, greater interest in Afro-Brazilian culture, which some men and women were able to turn into openings for more social inclusion and individual gain,? Hertzman said.

[btn-post-package]That?s not to say it was a completely smooth reversal of fortunes: As it became wildly popular, many Afro-Brazilian musicians were pigeonholed as samba artists early on, and they didn?t really have a chance to break out of that. If they had an interest in another type of musical genre, it was unlikely to be cultivated and nurtured. (Though they faced a number of different problems, such as official policies enforcing segregation, black musicians in America arguably had more artistic freedom than their Brazilian counterparts in the early 20th century.)

Also, it would hardly be accurate to say samba eliminated racial and cultural tensions in South America?s largest and most populous country. Nonetheless, it helped improve race relations in Brazil over time and provided a better life for many of its poorest and most alienated citizens, just as blues and jazz did in the United States.

?The attraction [between unequal peoples] usually is some combination of push-and-pull factors, with marginalized groups and individuals pushing for greater inclusion and recognition, while - for various reasons - dominant groups selectively pull in selected cultural manifestations and traits,? Hertzman said. ?Music seems to be of those manifestations that regularly hits the sweet spot between the push and pull.?

By Lyletta Robinson