Betsy Piland, August 25, 2018

Since computers were first introduced to the public, they?ve continued to get faster, cheaper, and especially, smaller. A machine that once took up an entire room can fit in your pocket. Now, a team of University of Michigan electrical and computer engineers has taken even tech tinier: the size of a speck of dust.

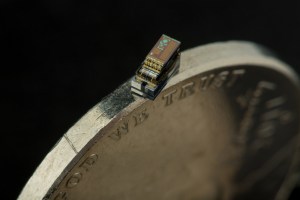

In March, IBM announced their development of 1-by-1 millimeter computer–just as Michigan professors were putting the finishing touches on something much smaller: the Michigan Micro Mote.

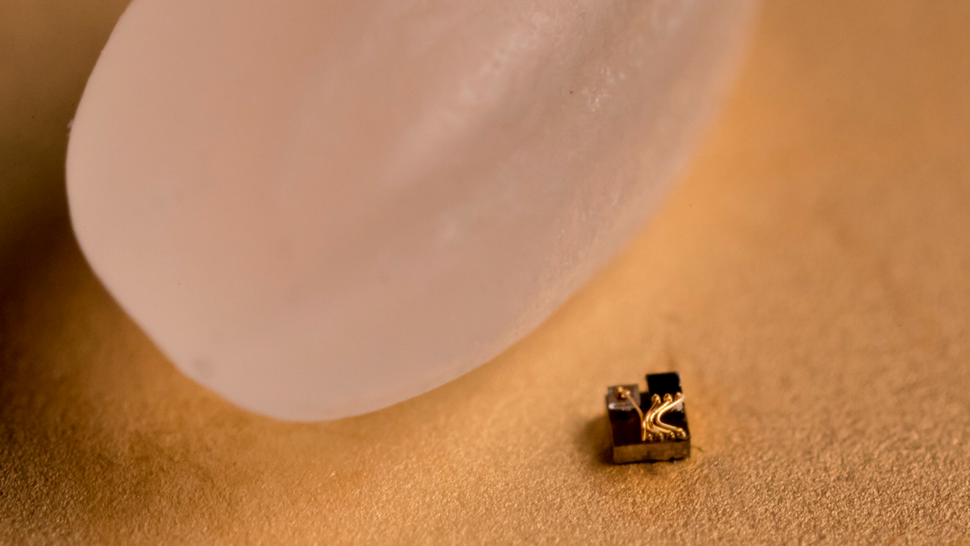

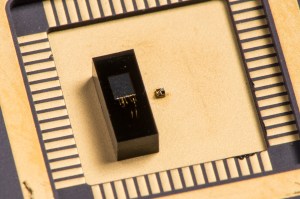

Michigan electrical and computer engineering professor David Blaauw explained that the point of creating this new computer was to scale down their previous version – that now resides in the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California – without losing essential functions. The Michigan Micro Mote is just 0.3 millimeters on each side.

Beyond the ?wow, cool? factor that a computer of this size boasts, it?s logical to wonder what something so small could be used for. Plenty, according to Blaauw. But still, he said, ?Sometimes you don't actually know what [the applications for something are] are until you build it.?

First, are implantable devices in the body to monitor illnesses. ?The smaller the sensor that you implant ? the better the reaction your body has to something implanted. It also makes the act of implantation much easier–for instance, you can implant with a syringe versus having to do an operation.?

Blaauw his team are working with physicians who are implanting the earlier version of their device into mice that have tumors, and using the device to measure the tumors? reaction to chemotherapy treatment. Another disease they are investigating is glaucoma.

?There?s a real need to measure the pressure inside your eye for management of glaucoma,? he said, ?and obviously for something to be implanted in your eye it'd have to be extremely small–a millimeter or less in size.?

He also described a variety of environmental applications, including using the device to track the migratory path of monarch butterflies or using it to measure the conditions of oil reservoirs.

So what makes something a computer? Blaauw explained that there are several criteria that are generally accepted when deciding if a device is a computer. First, a computer must have input–a way of acquiring data. We would think of this as a keyboard on our laptop, but for the Michigan Micro Mote, it?s the ability to sense pressure or temperature. Next, a computer must have output, like the display on we see on a cell phone. In the Michigan device?s case, it?s a radio link that communicates with an internet-connected base station. Finally, computers should be programmable and be able to do some kind of computation.

According to Blaauw there is only one sticking point that might find the Michigan Micro Mote not falling under the designation of a computer.

?Most computers have some kind of data retention,? he noted. ?Even when you unplug it, it would remember what previously happened and, when plugged back in, it would continue executing its program. [Our device] only works and remembers its programming as long as it is fed energy–in both cases, ours and IBM's, they receive their energy from light. If they lose their light source, they actually sort of reset and lose their previous data and programming.?

Blaauw has mulled over whether the Michigan Micro Mote (as well as IBM?s offering) qualifies as a computer. ?IBM says it's a computer. We're leaving it a little bit open. We're not challenging it, but we're not necessarily endorsing it as a full-fledged computer.?

With the opportunity to advance so many areas of research, the Michigan Micro Mote may not need to carry a hefty price tag. Like most manufacturing, volume is key. ?Of the 1 by 1 millimeter version, we've made thousands. Of these latest really small ones we've made a few dozen. The assembly process is still immature and difficult, so [they cost] hundreds of dollars.? But Blaauw said that eventually, with enough volume, they could be very inexpensive, possibly just pennies each.

That?s a big job for something you can barely see with the naked eye.

WATCH LIVE: Conference tennis championships for men and women.

WATCH LIVE: Conference tennis championships for men and women.