Scott Smith, October 22, 2017

Sometimes living big means taking big risks.

So it is with two recent Big Ten winners of the National Institute of Health Director?s New Innovator Award: Sarah Calve, Ph.D. of Purdue University and Jaehyuk Choi, M.D. Ph.D. of Northwestern University.

The NIH Director?s New Innovator award ?supports exceptionally creative early career investigators who propose innovative, high-impact projects.? It?s offered to those who have completed a doctoral or residency program within the last ten years and provides $1.5 million in project funding over a five-year period. In 2017, 55 researchers around the country received the award.

Dr. Calve, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Purdue who earned her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, received the New Innovators award for research which ?focused on the design and mechanical characterization of self-assembling constructs for musculoskeletal repair.?

Dr. Calve, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Purdue who earned her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, received the New Innovators award for research which ?focused on the design and mechanical characterization of self-assembling constructs for musculoskeletal repair.?

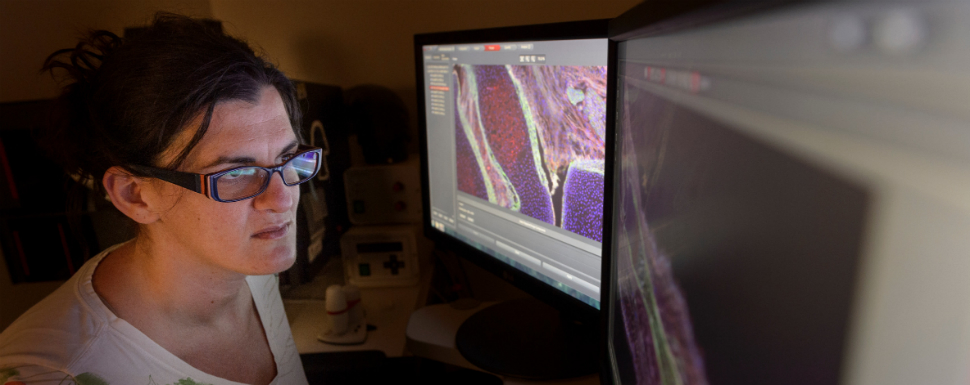

Specifically, she looked at how newts regenerate limbs using what?s called an extra-cellular matrix (or ECM). An ECM is formed when cells secrete molecules that offer support and structure to the cells around them. ?My lab has pioneered optical clearing methods to image the 3D ECM architecture of biomarkers deep within developing and adult musculoskeletal tissues,? she told LiveBIG via email. ?We will use these tools to test the hypothesis that an ECM-based template specified before tendon and muscle differentiation is necessary for the alignment and correct integration of load-bearing muscles and tendons during vertebrate forelimb development.?

The question at the heart of Calve?s work is how to create the right conditions for the regeneration of limbs, an innovation with obvious medical benefits. The stumbling block has been creating the kind of structures that would integrate with living cells. ?Despite decades of work, there has been little success in generating engineered scaffolds that effectively integrate into host tissue to promote musculoskeletal tissue repair,? says Calve. ?This is especially true for the interfaces between muscle and tendon, and tendon and bone. These regions are prone to failure from excessive mechanical loading and, in many cases, the interface cannot be surgically reestablished due to the complexity of the tissues.?

Calve says that dependence on artificial materials has hampered developments due to lack of study and knowledge about the way cells and tissues change during the creation of an ECM. ?My research aims to understand how nature establishes the links between muscle and tendon, and tendon and bone, she says. ?Our results will provide critical insight into the mechanisms that orchestrate musculoskeletal assembly and establish guidelines for regenerative therapies that aim to restore these interfaces in diseased and damaged tissues.

As assistant professor of dermatology and biochemistry and molecular genetics at Northwestern, Dr. Choi is also concerned with the health of the human body, but specific to T cells, which control immunity. His research ?seeks to understand how T cells integrate genetic, epigenetic, and immunological information in human health and disease,? according to the NIH. ?We utilize cutting edge genetic, epigenetic, and immunological approaches to define the molecular changes in individual immune cells in health and disease,? he said in an email.

As assistant professor of dermatology and biochemistry and molecular genetics at Northwestern, Dr. Choi is also concerned with the health of the human body, but specific to T cells, which control immunity. His research ?seeks to understand how T cells integrate genetic, epigenetic, and immunological information in human health and disease,? according to the NIH. ?We utilize cutting edge genetic, epigenetic, and immunological approaches to define the molecular changes in individual immune cells in health and disease,? he said in an email.

Dr. Choi is headed into uncharted territory of the human body. ?We have an incredibly complex immune system that is armed and prepared to fight against a near infinite number of potential microbial pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, or the like,? he says. ?How the immune system is able to maintain this diversity as we age is not clear. We hope that our work will elucidate this process."

Dr. Choi says that in the future his research may lead to a deeper understanding of the body?s overall immune system as well as cancer. ?If we are successful, our findings will have important implications in understanding fundamentals about human health but also may provide clues as to why the immune system falters in some people as they get older.

Calve and Choi both have lofty goals. In tackling them, each says it helps to aim high.

?I feel deeply privileged to do what I do,? says Choi. It may sound trite, but I start every day with two broad professional goals. 1) cure cancer and 2) answer big biological questions. I?m not sure we will ever accomplish those goals, but we will try.?

Calve notes that when she began her work, there was scant literature that described the way cells and their ECMs worked. ?The primary obstacle I encountered during my graduate studies was the lack of fundamental knowledge regarding the architecture of the tissues we were trying to engineer,? she says, crediting both her mentors at the University of Michigan and Purdue faculty who supported answering unanswered questions. ?When I joined Purdue, I found myself in a biomedical engineering department that was supportive of my interest in conducting basic biological research and fostered collaborations between the faculty. This unique environment enabled me to expand my toolset and begin to answer the questions I have been asking since I my graduate studies.?

Calve alludes to the long-term nature of this kind of study, but Choi puts more of a fine point on the difficulties researchers undergo. ?Rejection is a fundamental part of the game,? he says. ?Before getting this award, I have had a number of grants rejected. My research team and I just persevere with the hopes that if we are doing good science, committed to improving human health, things will turn around.?

What Choi describes is exactly the kind of ?high-risk, high reward? work the NIH Director?s Innovator Award is designed to highlight. For Calve and Choi, the expectation of risk is never far from their minds.

?I feel deeply privileged to receive this award. It?s quite an honor,? says Choi. ?That said, it?s time to get to get to work. It is time to put our hard hats on and to try to accomplish the things we set out to do in the award.?