John Tolley, November 28, 2017

If things go according to plan, late next summer NASA is going to the Sun, that big, bright, exceedingly hot, plasmic, don?t-look-directly-at-it, skin-scorching ball of fire that really pulls our solar system together.

The Parker Solar Probe Plus will travel closer than any man-made object has before to our local star, swooping to within 4 million miles of the Sun?s surface on a few of its 24 orbits.

Hitching a ride on the probe are instruments developed by University of Michigan associate professor of climate and space sciences and engineering Dr. Justin C. Kasper who is the principal investigator for the Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) Investigation team.

One of only two suites of instruments outside of the probe?s carbon-composite heat shield, Kasper?s SWEAP equipment includes a Faraday Cup that will literally be capturing samples of the Sun. The device, built by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, collects positively-charged particles in order to discern the velocity and direction of solar forces.

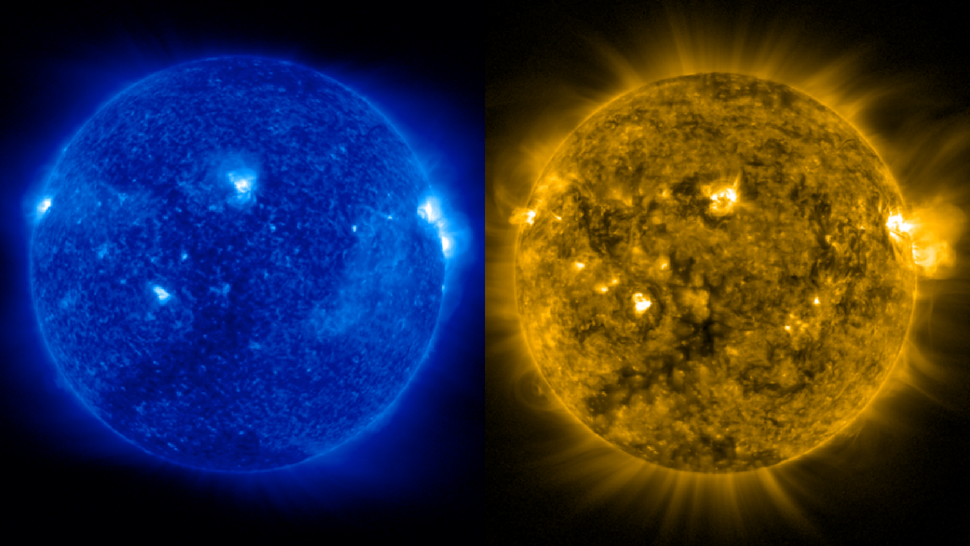

The mission to the Sun is more than 50 years in the making, and is the culmination of countless hours of theoretical work here on Earth. Researchers are hoping to broaden our understanding solar winds and flares, electrically-charged events which can wreak havoc on a society that is becoming ever more reliant on technology.

?In addition to answering fundamental science questions, the intent is to better understand the risks space weather poses to the modern communication, aviation and energy systems we all rely on,? said Kasper, speaking to UM?s CLaSP News. ?Many of the systems we in the modern world rely on-our telecommunications, GPS, satellites and power grids-could be disrupted for an extended period of time if a large solar storm were to happen today. Solar Probe Plus will help us predict and manage the impact of space weather on society.?

Kasper?s specialty is designing instrumentation for the most extreme conditions of Space, from the farthest reaches of our solar system to, now, the ?surface? of the Sun. Using data culled from the Voyager mission, he was one of the first scientists to detect the termination shock wave that surrounds our atmosphere. In addition to being the principal investigator for the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Kasper has served on advisory boards at NASA, the National Science Foundation and the National Academy of Sciences.