Scott Smith, October 8, 2017

Doug Bradley is a veteran of the Vietnam War. But his view of the United States' most contentious military conflict is different than many of those who saw combat.

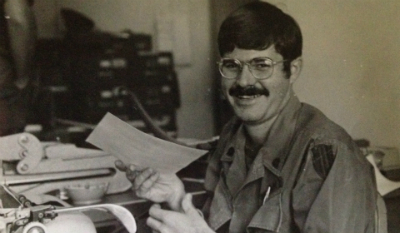

Drafted in 1970, Bradley served as an information specialist in the U.S. and in Saigon. Off the front lines, he saw a side of the war that often goes unreported, even through in-depth profiles.

Since his discharge, he's written and worked on behalf of veterans. His first book, DEROS Vietnam: Dispatches from the Air-Conditioned Jungle offers fictionalized accounts of rear echelon personnel. After decades in various roles at University of Wisconsin's communications departments, he now lectures and teaches lessons of the war through the music and media of the time in a course called "The U.S. in Vietnam: Music, Media and Mayhem. A book he co-authored, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, explores how music wove through the experience of those who served.

BTN LiveBIG spoke with Bradley about his thoughts on the new Ken Burns/Lynn Novick Vietnam miniseries, what stories about the war are still left untold and what lessons we can learn from all of it.

BTN LiveBIG: Have you seen the Ken Burns/Lynn Novick Vietnam miniseries?

Doug Bradley: I have.

BTN LiveBIG: It seems like you're both interested in capturing stories that have been lost in the discussion of the war, particularly with your focus on backfield stories.

Bradley: I was impressed, and frankly pleased, that there were so many Vietnamese involved in the program. I thought it was long past time that we understood that we were in somebody else's country and somebody else's civil war. And damaging so many other lives.

But as I've indicated in the things that I've written about, there were a lot of us in the rear fighting maybe a different war or supporting the guys who were doing the fighting and dying. And that story continues to get lost. And those roles are important. It's certainly it's not as heroic. I understand that. The level of bravery? I wouldn't even use the term. But it?s just something we ignore and, I think, overlook. That sort of diminishes our whole perspective of what war is about, if not what that war was about. Besides the killing and the dying.

BTN LiveBIG: Are there themes or similar stories that people that you served with all cite?

Bradley: What was happening in America was what was happening to us as a generation: we were defying authority, we were fighting with our parents, we were pushing back against the government. That happened in the Army. That's a story that doesn't get told.

You know the G.I. resistance movement - the Vietnam Vets Against the War – we really don't pay a whole lot of attention to that because it was happening everywhere in our generation.

Drugs. How we were beginning to use different inebriants than our fathers and their generation did.

The racial situation in America at the time. It?s a powder keg in the army. We had more, per capita, minority soldiers [than in the general population]. And we all got guns in this thing.

If this was a tinderbox in America you can imagine what it was like, at times, in Vietnam so everything that was happening in America was happening in spades in Vietnam, plus you were in a war zone.

BTN LiveBIG: There?s this widely accepted canon of Vietnam-era songs that come up often: Doors, Buffalo Springfield, Creedence. Mostly white rock bands, aside from Jimi Hendrix. But I'm curious about songs or artists that were descriptive of the war experience for black or Native American or Latino soldiers.

Bradley: I think back to one conversation we had with this wonderful guy Charlie Trujillo, a Chicano vet from California who said ?Where was our music? When there used to be fights over the jukebox over whether you?re going to play Sam and Dave or Merle Haggard, where's our music? Nobody?s saying we get a chance to listen to Santana.?

To me, it?s become easy to mythologize the 60s because it's too difficult. It's not black and white it's not hawk and dove. It's not right and wrong. It's much more complex. And the music, too.

Any movie about the Vietnam era, the protest movement is going to have [Buffalo Springfield?s] ?For What It?s Worth? in it. But if you look back at the genesis of that song Stephen Stills didn?t write that about Vietnam. It was about a protest but it was a bunch of 18 year olds trying to get into a club in L.A. because they changed the curfew laws.

BTN LiveBIG: Why is it that music, in particular, seems to be a really instructive way to reveal the history of a particular time?

Bradley: My very pedestrian understanding of brain research is that music and sound is right next to the part of the brain where memory lies. So you get this kind of association and connection.

There?s music from all wars but the music of that war was so prevalent and persistent because the Army knew the importance of music to us. And so especially in the rear we got access to music in a variety of ways.

The soldiers of the current wars have access like we did. They have access to the entire soundtrack of music history. But it's not shared. They put on their headsets. We shared the music.

BTN LiveBIG: For students taking this class now, this was more than 50 years ago. Is music a way to help them contextualize this and not have them think of it as history, but as something that has current resonance?

Bradley: The young people that are coming into our class now were born in the late 90s. It's ancient history. But they know the music and it's astounding. They know Smokey. And Otis. And Hendrix and The Doors and The Beatles and Dylan and on and on and on. And they're familiar with the music. And the music then becomes the thread that we can use to excite them. We bring veterans in to personalize the music and the experience. We get to it through the stories that the veterans tell us and they tell it through music. Good bad and ugly.

BTN LiveBIG: Is there a lesson from war that we keep forgetting or has been left unexplored?

Bradley: You're talking to a veteran who lost friends either during that or afterwards when they got poisoned by Agent Orange or struggle with nightmares and flashbacks and PTSD their entire lives.

War is not the answer. I know that makes me sound like some hippie protester. But when you see it up close you realize that it's a terrible thing. I mean it?s the worst thing we can do as humans. So we need to figure out other ways to resolve conflict. If we do this, don?t put the whole moral burden of waging the war on the shoulders of the men and women who have to do what they do in our name.