Scott Smith, June 12, 2017

Great achievement has no road map, which is to say accomplishment isn?t always a linear journey with a fixed destination. Planetary science, with its vast scope, is particularly suited to this maxim.

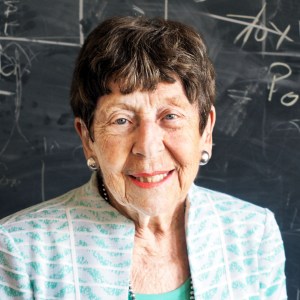

Last week, the career and work of University of Michigan professor Margaret Kivelson made it clear just how circuitous and dense with possibility exploration of our solar system can be.

Last week, the career and work of University of Michigan professor Margaret Kivelson made it clear just how circuitous and dense with possibility exploration of our solar system can be.

Kivelson was awarded the 2017 Kuiper Prize, an annual award bestowed by the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society ?to scientists whose achievements have most advanced our understanding of the planetary system.?

So, pretty high bar there, but about what you?d expect for an award named for the guy who discovered the Kuiper Belt.

What did Kivelson do to attain such lofty heights? She merely established, in the words of the AAS, "our best chances for discovering life beyond Earth" through her research into the outer solar system.

Oh.

Here?s a brief, but incomplete due to space constraints, sample of Kivelson?s professional accomplishments:

- Extensive study of data from Galileo and Pioneer 10 and 11 spacecrafts during the 1970s which led to…

- The discovery of an internal magnetic field on Ganymede, a moon of Jupiter and the largest moon in our solar system which led to?

- Evidence that Europa, another moon of Jupiter, contained a sub-surface ocean which meant that most likely…

- There is life on other planets. Plus, there?s her extensive work on…

- The wave frequencies and behaviors of magnetospheres. All of which adds up to a tremendous influence as?

- Author or co-author on more than 350 publications that have been cited more than 12,000 times as well as her standing on…

- NASA's Advisory council and the National Research Council's Committee on Solar-Terrestrial Research

- Oh and she literally wrote the book on space physics

Other highlights of Kivelson?s career include studying under Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger while at Harvard, a stint at Imperial College London, working at the RAND Corporation and chairing the department of Earth and Space Sciences at UCLA.

Moreover, she did this in a time when she was often one of only a few women pursuing her chosen field. She was, for example, the only woman in her class at Harvard under Schwinger. She was also criticized for being a ?working mother? in the 1950s. She spoke extensively about these challenges with Fran Bagenal, a fellow planetary scientist.

Contrary to this thinking, her family life and connections to students were strengths in her work. And here it?s fitting we give Kivelson the last word on her achievements, from a 2007 article she wrote for the Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences titled ?The Rest of the Solar System.?

Most critical to my career was the extraordinary opportunity to pursue research in a great university working with accomplished and helpful colleagues and students. That would not have been possible without encouragement and support from my husband and children. Students, both undergraduate and graduate, have kept me rethinking what I think I know. I started in the field of space physics at its inception, when so little was known that it was straightforward to find something interesting that had not yet been worked out. I was in the right place at the right time to get involved in studies of the outer planets. And to my great good fortune, it turned out that the tenuous plasmas of planetary magnetospheres, fascinating in themselves because of the beauty of the physics that they reveal, also hold clues to what is going on deep within the bodies that they envelope.