Courtney Jacquin, June 3, 2017

For centuries, prosthetic limbs have been used to help people move through their everyday lives. Recent technological advancements give users the freedom to move with ease, with prosthetic limbs often acting just like biological arms and legs.

But what if prosthetics could be used to treat diseases within the body as well as substitute for external limbs?

That?s exactly what Dr. Martin D. Burke, a professor of chemistry at University of Illinois and interim dean of research at Carle Illinois College of Medicine recently discovered along with a team of researchers from Harvard Medical School and Northeastern University. The group recently published its findings in the May 12 issue of the journal Science.

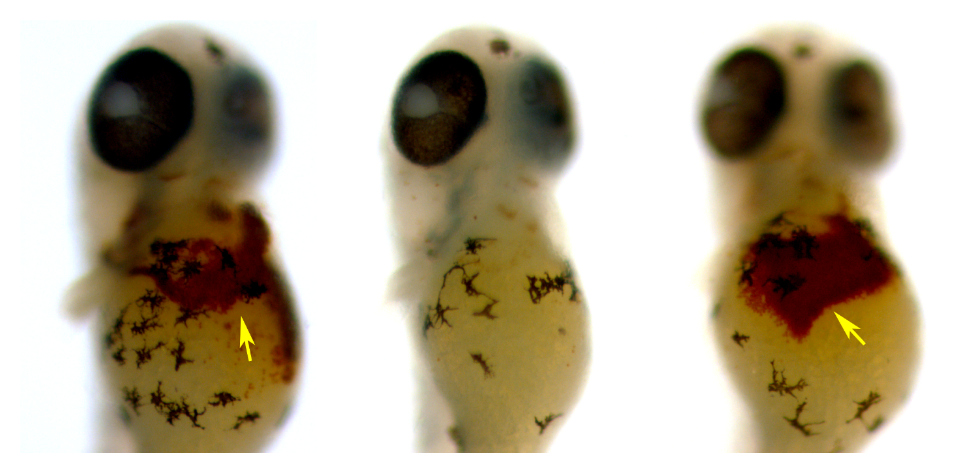

Burke and his team found that a small molecule can transport iron in human cells when proteins that normally do the job are missing, a condition that can cause severe anemia.

Hinokitiol, a substance found from the bark of a Japanese cedar tree, is the molecule, and it works by transporting iron across cell membranes that are missing transport proteins. In anemic patients, iron builds up, but the introduction of this prosthetic-like molecule helps restore the normal flow of iron.

?We?re excited that it represents a first example of a small molecule replacing missing proteins and restoring physiology in animals, and we think this bodes well for the general concept of replacing missing proteins with small molecule counterparts, which we think could represent a really colorful new way to think about treating this type of disease,? Burke says.

Burke became interested in this concept all the way back in medical school when learning how typical medicines work.

?If you're sick because you have too much protein function, most medicines work by binding to such proteins and turning them off,? Burke says. ?What also really struck me is that if you're sick not because of an excess but instead some type of deficiency of protein function, you're fundamentally missing something, this classic paradigm of pharmacology falls apart.?

In research, Burke and his team found the challenge of working with proteins is that they?re extremely sophisticated and finding an exact replica would be difficult. What he learned, however, is that imperfection was OK, and most of the functions could be recreated without a perfect replica.

?If you are missing a hand, a pretty simple prosthetic device can actually be very helpful because your other hand works harder to get creative and figure out ways to solve problems with an imperfect mimic of an actual human hand,? Burke says. ?We found the same thing to be true at the molecular scale - a pretty imperfect mimic of this missing iron transporter actually got the cells back to almost a normal state, suggesting that there is an inherent robustness of the living system.?

In introducing this molecule, or an optimized variation, in humans, Burke hopes he can help those with anemia as well as a rare disorder called ferroportin disease, which is a genetic mutation of the protein Burke and his team targeted in their research. Burke is also examining the effects of arthritis and Lupus on the body?s regulation of iron, which leads more than 10 million people to suffer from anemia.

?Our hope would be that perhaps this same type of approach might even be helpful in this much larger patient population,? Burke said. ?So we're hopeful optimistic that may open the door to figure out a different way of addressing this really important disease.?