Courtney Jacquin, December 30, 2016

Photosynthesis is, seemingly, a very simple process. Even someone with the most limited biology knowledge knows that plants and other organisms are fueled by sunlight.

But it?s not that simple.

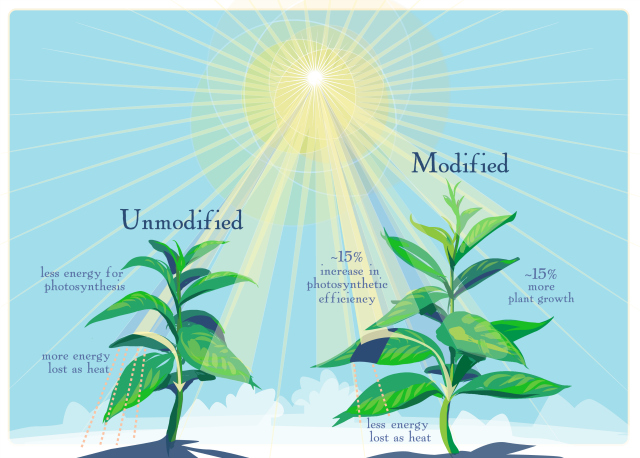

Plants aren?t always working at 100 percent efficiency with photosynthesis. In fact, plants tend to protect themselves from direct sunlight, slowing down the process. Recovery time can be slow, hindering a plant?s productivity.

When it comes to crops, productivity is important. And that?s where University of Illinois plant biology and crop sciences professor Stephen Long comes in.

?My research around photosynthesis looks at the overall process rather like a production line, and then how we might make that production line more efficient,? Long says.

Over the past decade, Long and his team have been working to identify ways to increase recovery time and overall productivity.

Along with researchers from the University of California Berkeley, Long identified proteins linked to the ?relaxation? of photosynthesis. After a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation four years ago, Long and researchers at Illinois genetically modified tobacco plants, boosting specific protein levels, which led to a 14 to 20 percent increase in yield.

?When a leaf goes into the shade, it takes some time to readjust to the shade,? Long explains about the relaxation process. ?It?s rather like, reactive sunglasses, that when you?re in the sun they?re dark. When you?re in a dark room, it takes a while for them to adjust, and a leaf is the same. But instead of seconds it?s taking minutes, even half an hour.?

This is where Long?s research began 12 years ago, identifying through computational analysis this recovery time can lead to a loss of 20 to 40 percent of productivity. For crop yields, that?s a huge loss in potential output.

From there they found the genes connected to the specific proteins and genetically modified tobacco plants, testing the plants first in the lab then in the field.

Long and the team chose to test their work on tobacco plants because of the plant?s ease of genetic modification.

?We used tobacco because it was quick, but the process is identical in soybean, in corn, in rice, in cassava, so we?re now testing this in a range of other crops.?

Because of Long?s funding from the Gates Foundation, which focuses on fighting world hunger and poverty, his focus now will be primarily on crops of Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, including rice, cowpea (black eyed peas) and cassava.

Increasing crop productivity, however, is a problem that could soon affect everyone.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the world will need to produce 70 percent more food than it is currently producing by the year 2050. Not only will there be an estimated 2.3 billion more mouths to feed by the middle of the century, populations are becoming more and more urban, which leads to more food waste, according to Long.

?Seventy percent is a lot, and if the present rate at which we?re improving our crops, we?re not going to get there, so we need new innovations which can allow us to get there. If we don?t, it means prices will rise, the poorest in the world will clearly suffer the most.? Long says.

An increase in photosynthesis productivity is not just potentially the future of agriculture, it could be the future of preserving our planet.

?[Not increasing crop productivity] would also incentivize expanding agriculture and moving onto more land and more damage to the environment. If we can get that food on the land we?re already using, we avoid those spillover problems.?