Betsy Piland, July 18, 2016

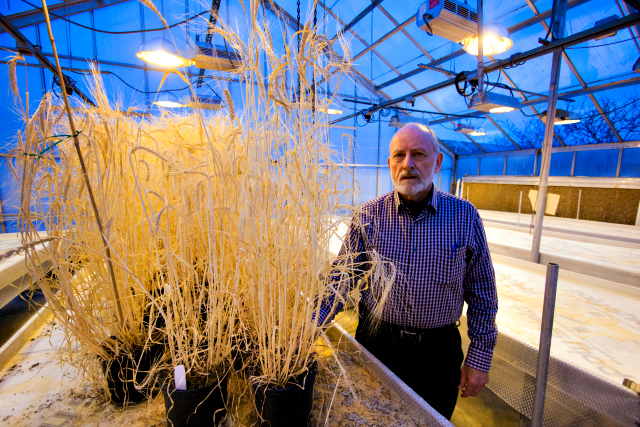

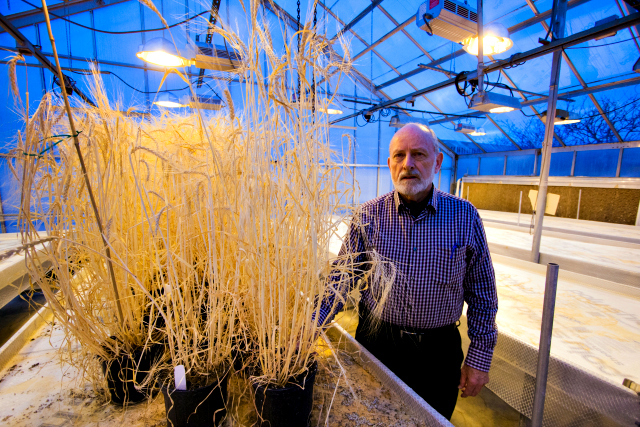

Russell Freed, Michigan State University Professor of International Agronomy, puts it very simply when asked to sum up the buzz surrounding the imminent resurrection of Spartan barley across farms and microbreweries in the Mitten State.

?If you don?t understand the joy it would bring to imbibe beer made with Spartan barley, well, you mustn?t be a Spartan.?

In the world of craft beer, much of the appeal is the story you can tell with your product. Beer brewed with Michigan-grown Spartan barley? That possibility has sparked the enthusiasm of local maltsters and microbrewers alike.

Freed is well-versed in the history behind this grain, which is native to Michigan and, specifically, MSU. ?Originally it was a variety developed by Frank Spragg,? says Freed. ?He was a professor at MSU and he made the cross between two Michigan varieties, Michigan black barbless and Michigan two row, in 1916.?

Plant breeding takes time, sometimes ten or more years until the variety is stabilized-growing with the same characteristics year after year. Spartan barley was released to farmers in 1928; it took 12 years to make sure the plump seeds all bred true with high yields and resistance to disease and insects. After that, Spartan barley?s popularity grew quickly, used by many farmers throughout Nebraska, North and South Dakota and Colorado in the 1930s and ?40s. ?[A USDA report] said that in 1957, 27 percent of the Nebraska barley acreage was Spartan barley,? says Freed. ?That is some significant acreage in the northern tier of the Midwest.? Freed says any grain covering more than 10 percent of an area means the farmers and maltsters were impressed with the variety.

After a 40-year reign, Spartan barley fell out of popularity. Another surge of plant breeding in the 1960s resulted in crops with higher yields and better malting qualities.

As part of her work with farmers of past generations, Ashley McFarland, coordinator of MSU?s Upper Peninsula Research and Extension Center, learned about Spartan barley?s history and was impressed-and intrigued. "My crop technician Christian Kapp and I discussed it and approached Dr. Freed because we knew if anyone could get his hands on [Spartan barley seeds], he could."

So Freed wrote to the USDA germplasm bank where they store heritage varieties that have been released in the U.S. as well as ones collected from around the world. The USDA bank in Aberdeen, Idaho was able to send Freed five grams of Spartan barley seed. That allowed him to do a first crop of 80 plants in a greenhouse and from there continue to harvest and plant seeds, even growing some in Arizona over the harsh Michigan winter. Freed said they will continue to increase the seed supply until it is enough to distribute to farmers. ?It does take several years, when you go from five grams to needing a couple hundred bushels. It isn't fair to give just three bushels to one farmer.?

If the seed production and the resulting barley crops take off, it could be a boom for both the Michigan agriculture and craft brew industries alike. Ryan Hamilton is an experienced maltster for Pilot Malt House-the largest in Michigan-and specifically looks for locally sourced ingredients. ?As a maltster, I rely solely on local agriculture and local value chains. I'm very excited about the breeding potential that Spartan may hold for developing new elite varieties that are more well suited to cultivation in Michigan.?

Spartan barley fell out of wide use for a reason. But as McFarland explains, ?[A majority] of the barley production is out west where their weather is much more arid. So researchers are revitalizing these old varieties that were once bred for these particular regions to see if they possess any particular favorable traits for potential modern breeding programs. We're not there yet to know if Spartan has potential for that, but it is exciting to bring it back to see how it performs."

Freed believes that the aspects of the plant that were considered a drawback at the time will be a benefit to the microbrewers. ?Out in the Dakotas they grow significant acreages of barley for the Bud Lights, the Miller Lites, beers that want to have the same taste today, tomorrow, and year over year. There?s a very high degree of specification for those kinds of barleys. With microbrews, Spartan [barley] this year might taste different next year because of climatic conditions, the proteins, and other aspects.? Every batch of beer brewed with Spartan barley will have a distinct taste-and that?s a good thing for a community where small batch varietals are in demand.

Hamilton says that the appeal of local barley goes beyond the microbrewers. ?For consumers, the growing interest in a return to local food systems makes heirloom or heritage plant varieties very appealing. Spartan has a 100-year-old pedigree that is a direct link to a time when nearly all food systems were localized.?

Beer lovers will have to be patient though. It will be about two years before bushels of seed can be distributed to farmers. Freed said that after this summer?s harvest they?ll have a much better idea of a timeline. ?But you have to look at the big picture. We don't want any unhappy farmers where they heard Spartan barley is available and they weren't able to get seeds."

With the popularity of locally sourced ingredients and the affection for its collegiate affiliation, Freed believes there?s more to the Spartan barley?s comeback than just beer. ?It's so exciting to see something that was made 100 years ago still has relevance in the 21st century.?

By Betsy Piland