BTN.com LiveBIG Staff, June 19, 2016

To most people, a small bead and fragment of metal found in Alaska just south of the Arctic Circle wouldn?t qualify as particularly significant. But for H. Kory Cooper, associate professor at Purdue, they reveal a world of historical possibility.

Cooper, who?s part of Purdue?s Department of Anthropology and School of Materials Engineering, recently examined the metallurgical characteristics of these objects, with funding from the National Science Foundation?s Division of Polar Programs Arctic Social Sciences. They were originally discovered a few years ago by Owen K. Mason and John F. Hoffecker from the University of Colorado, in an area along the western coast of Alaska inhabited by the Inuit centuries before.

?One of the reasons I was brought in on the metal finds is that for several years I?ve been doing research on native use of copper in Alaska and northern Canada,? Cooper explained.

His analysis of the handful of objects excavated by Mason and Hoffecker showed that they were a copper alloy with lead and tin mixed in. In historical terms, that?s a big deal because the ancient Inuit weren?t doing that kind of metalworking, meaning those items must have come from somewhere relatively far away.

?This is not native copper,? Cooper said. ?It?s the first time that anyone has found something that would be dated in a pre-historic time in Alaska. To me, it was a matter of time before we found something like this.?

He said the objects, one of which appears to be part of a tiny buckle that would have been manufactured in cast mode, were likely made somewhere in Eastern or Central Asia - perhaps China.

?We don?t know if this is actually made in China,? he added. ?We?re not saying this is a Chinese object per se. That was the closest thing we had as an example. Probably some part of Eurasia.?

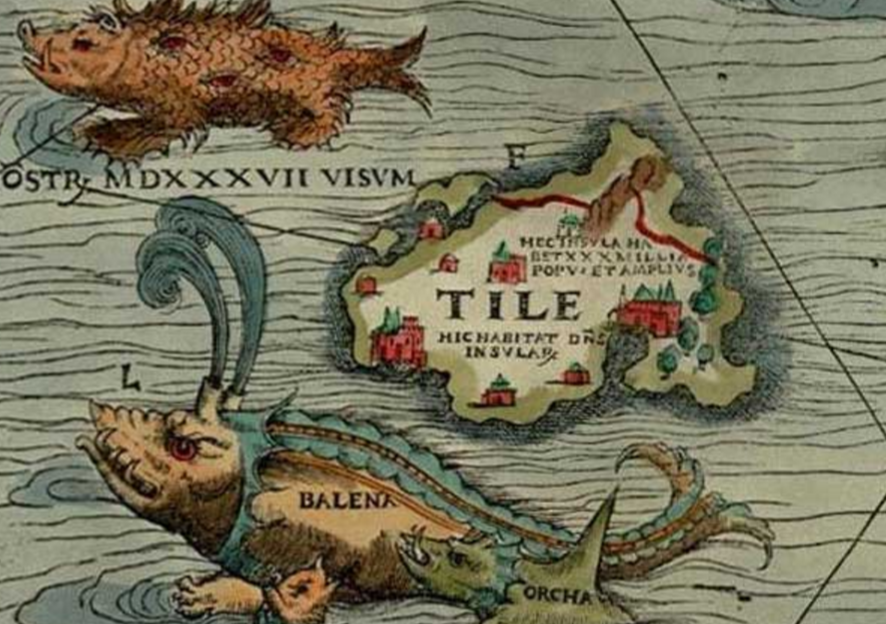

Does that mean trading ships from China or some other East Asian civilization sailed up to Alaska to do business with the Inuit, potentially ?discovering? the Americas before Columbus the same way the Norse did on the Atlantic side? Cooper said it was possible, but it?s more likely that the objects slowly worked their way up through trading networks in eastern Siberia before crossing the Bering Strait.

If that?s the case, it would demonstrate two things. First, the ancient Inuit must have had cultural and commercial reach that spanned several thousand miles and connected them with several other ancient civilizations. And other factors suggest that was indeed true, Cooper said.

?Indigenous people on either side of the Bering strait were speaking very similar languages,? he explained. ?There was active trading and even warfare among the Inuit across the strait. These trade networks already existed for certain kinds of things. Groups on the Siberian side were interested in caribou and walrus pelts [from the Americas].?

[btn-post-package]Secondly, the geographic movement of these items would further show how, in pre-modern times, things were simply used for a much longer period. In an age of industrial manufacturing, most objects tend to be seen as highly replaceable, and are often disposed of after a few years. Not so for people of ancient civilizations.

Cooper said the artifacts discovered in Alaska might have been used for decades or even centuries before arriving there. And he pointed to very old Chinese coins in places like the Bay Area as supporting this premise.

?It?s not uncommon to find Chinese coins dating to the medieval period along the West Coast of North America,? Cooper said. ?Immigrants brought them over as late as the 1800s. They stayed in circulation for a long time.

?The world is composed of middlemen,? he added. ?Objects keep moving.?

By Brian Summerfield